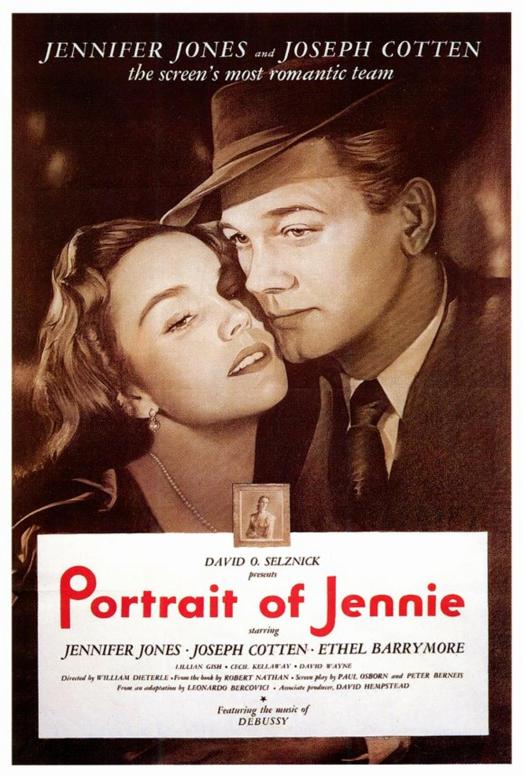

Glimpses of the Portrait of Jennie in 1948:

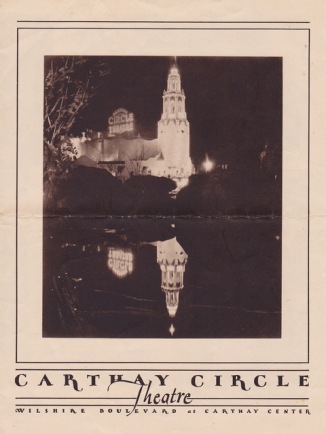

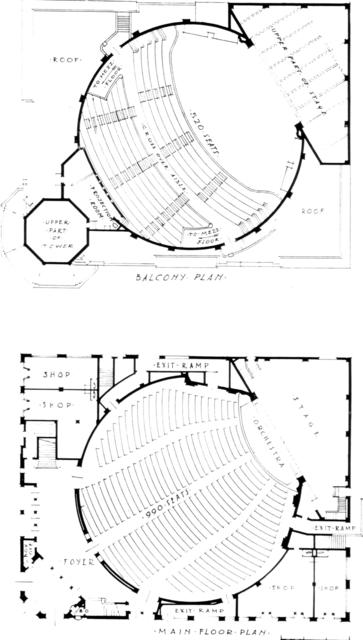

Portrait of Jennie had its general public premier on Christmas Day, 1948, at the Carthay Circle Theater, located at 6316 San Vicente Boulevard, Los Angeles, California; a more than fifteen-hundred seat theater, with nearly one-thousand on the main floor. The opening was seen in the afternoon, with the theater opening its doors at noon.[1] This was far from the first viewing of what is now considered a classic film of the Golden Age of Hollywood…

On November 18, 1948, Portrait of Jennie was previewed in San Francisco, unfortunately, Jennifer Jones was unable to attend, because she was in the hospital for an appendicitis operation; the attack occurred on the day prior. She was confined to rest at the Good Samaritan Hospital, not released until November 29.[2] As was the custom for producer David Selznick, the premiere of Portrait of Jennie was viewed exclusively in veterans’ hospitals, date unknown but prior to November 18;[3] the first preview of, Jennie, for journalists, was not for the professional media, but for the high-school newspaper editors around Los Angeles. This special advance screening was in the first week of December, 1948, at the Selznick Studio.[4]

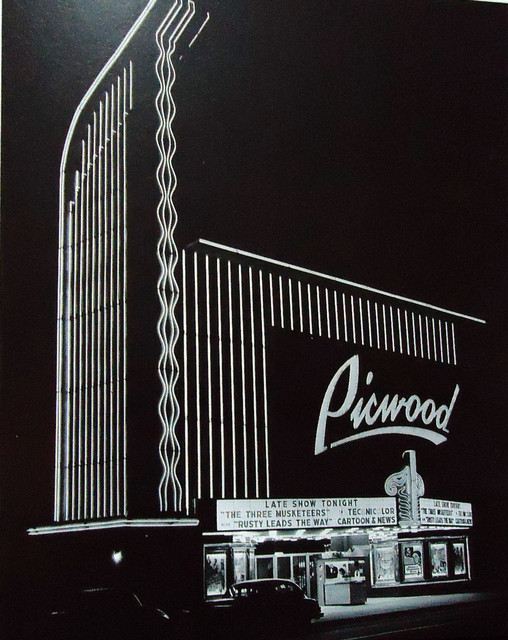

The Portrait of Jennie saw a pre-Christmas preview for the professional writers at the yet unopened eleven-hundred seat, Picwood Theater located at 10872 W Pico Blvd, at the corner of Westwood Blvd., Los Angeles, California. The Picwood was owned by Phil Isley, Jennifer Jones’ father and her uncle, F. M. Isley. The Isley brothers also owned the Meralta Theatre in Culver City, California and the Lankershim in North Hollywood, as well as theaters in Texas. This move by Selznick was to help out Jones’ father (Jennifer Jones and Selznick would soon marry: July of the following year) who was suing Paramount Pictures, amongst others.[5] The suit alleged that the companies named were preventing Isley’s Picwood Theater from obtaining first run films on the same opening day as other Los Angeles area theaters. Included in the suit were eight producers and five “John Doe” corporations.[6] In the interim Phil Isley settled for second run status and opened the doors of the Picwood on Christmas Day, 1948 to the public.[7]

Theater owners and operators got their chance to see, Portrait of Jennie, with the next viewing which occurred in the New Year, when a trade screening was scheduled for early January, 1949, in New York City.[8]

The national release date of April 22, 1949 for Portrait of Jennie is incorrect, although many cities saw the film in the late spring of 1949; this was by no means a national roll-out with a hard and fast single day premier. Play dates in April and May of 49, were not consistent with a nation-wide release; this was a soft opening with premiers throughout the summer.

Portrait of Jennie was seen in four additional cities prior to that release date of April 22, which is made reference to by so many modern sources. The openings in these four cities are in today’s market designated as limited engagements. With special previews, grand openings and special engagements, Portrait of Jennie, was seen from November of 1948 through the third-week of April without any particular target date of release. In many ways it was a weak approach for Selznick to wait for the Academy Award results to make available his fantasy-romance across the country. While most reviews were kind, any negative reports tamped down box-office receipts and as some industry insiders believed, Jennie played better to sophisticated audiences, mainly in the larger metropolitan areas.[9] Often Jennie was coupled with a mystery, comedy and even a western [10] and in the smallest markets the film saw little or no advertising. Quite a few communities did not see Jennie until autumn of 1949 and at least one theater had a special Christmas Day, 1949 showing.[11]

And now to the four cities that saw the celluloid Portrait brought to life by David Selznick, before the rest of the country did:

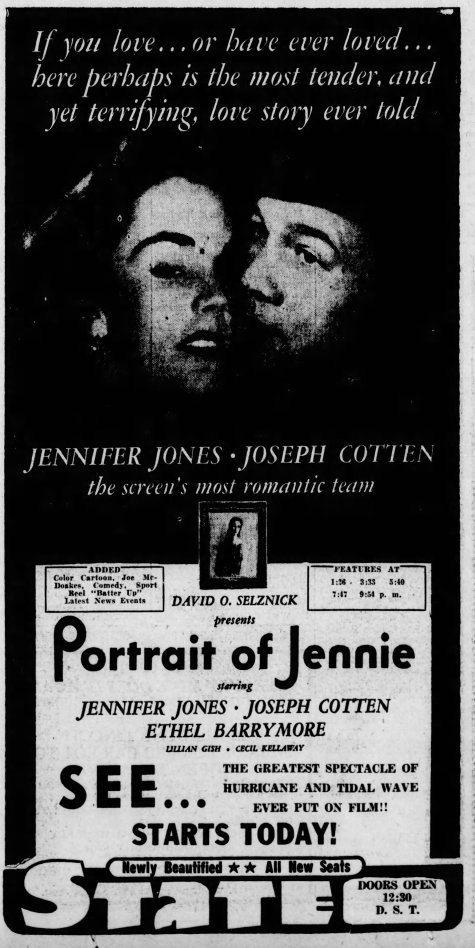

- Boston saw the Portrait of Jennie opening in the middle of March, at the Esquire and Mayflower Theatres; the Esquire instituted student pricing before 5:00 PM, daily, except Sundays.[12]

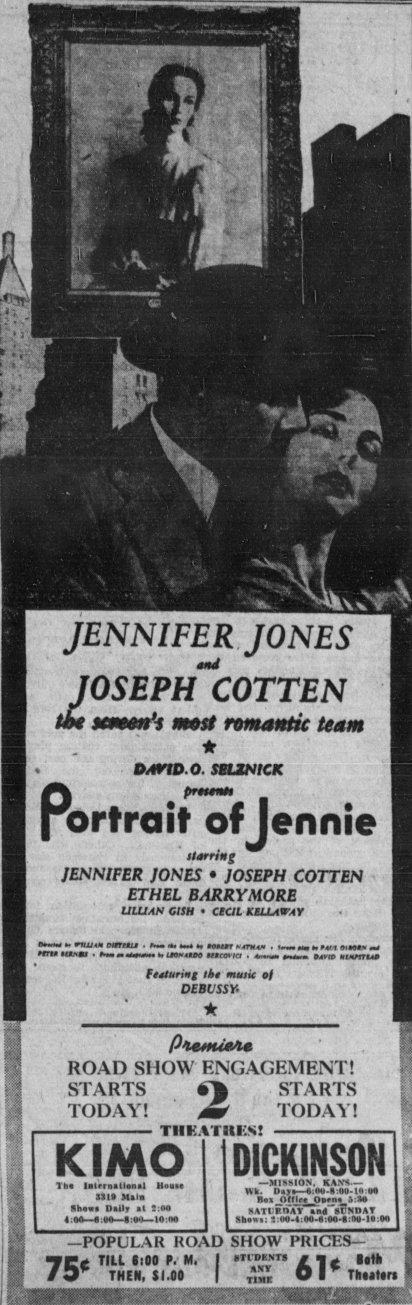

- Next, Portrait of Jennie was seen as a “premiere roadshow engagement” in Kansas City beginning on Thursday, March 24, 1949,[13] this was a two-house opening, at the Kimo Theater near downtown Kansas City, Missouri, at Main St. and 34th St… The second theater was the Dickinson, in Mission, Kansas (a suburb to the southwest of downtown KC), at 5909 Johnson Dr, just west of Woodson Rd…

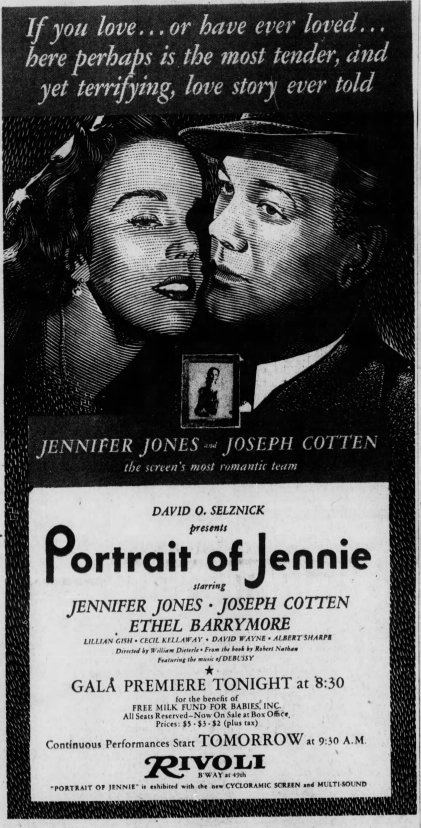

- Then there was the gala premiere at the Rivoli Theatre, Broadway and 49th, in New York, which was on Tuesday evening at 8:30, March 29, 1949. This special viewing was to benefit the, Free Milk Fund for Babies; the entire proceeds of the premier went to the charity. Those in attendance where a who’s who of society, with Lord and Lady William Waldorf Astor, Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Vanderbilt, Randolph Hearst, Jr. and his wife, along with Mr. and Mrs. John Randolph Hearst, and the Count and Countess Igor Cassini.[14] Jennie would run seven weeks at the Rivoli posting good box-office till the end.[15] A rather large supper party followed the charity premiere of Jennie, hosted by the Hearsts, at their home.[16]

- April 18 was the premiere for Jennie in our nations’ capital; this at the Trans-Lux Theatre of Washington, D. C., on 14th Street between H Street and New York Avenue NW.[17] The First Lady, Bess Truman headed the list of sponsors for the premiere which benefited the David Memorial Goodwill Industries; this was D. C.’s workshop for the physically impaired; the chairman of the sponsoring committee was Mrs. Julia Roberta Vinson, the wife of the Chief Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court, Fred Vinson.[18]

Below the Paint: The Hiring for the Canvas

Although Portrait of Jennie premiered in December of 1948, and began filming in early 1947, still the story of its production began nearly five years before Christmas of 48…

In December of 1943, M-G-M bought Portrait of Jennie, a popular novel written by Robert Nathan in 1939.[19] Michael Arlen was set to adapt the novel for MGM (he had just completed collaborating on, The Heavenly Body) and the speculation was that Susan Peters, fresh off of, Song of Russia (which was released February 10, 1944) would star in the title role.[20]

Then in early January of 1944 David O. Selznick acquired the screen rights to Portrait of Jennie,[21] and Jennifer Jones although unofficially announced[22] for the part, was referenced as the likely star and close friend of Selznick, Joseph Cotton was publicized for the role of Eben on January 20, 1944.[23] Then the gap, three years between the initial casting of the stars and the actual production’s beginnings; time spent in development and technical preparation.

The First Brush Strokes of Jennie:

The location production unit for, Portrait of Jennie, was on the east coast during the winter of 1947, beginning photography on February 14;[24] shooting scenes in Central Park, Boston Harbor and other spots on the east coast.[25] The filming in Central Park was blessed by snow, which the property men were preparing to utilize an artificial snow-blanket over grass until the fortuitous event.[26] Director William Dieterle while in Central Park, in a most theatrical manner proclaimed as he saw the bronze likeness of Shakespeare: “Cast him.”[27]

Set construction was already in process in April of 1947, with William Saulter supervising the building of the sets for the fantasy, based upon the designs by Joseph B. Platt.[28] The Moore’s Alhambra Bar set when ready to be broken down, was used for a party thrown by the publicity department for Jennie, and attendees (writers) were given beer mugs which had been inscribed with “Moore’s” for the film, as party favors.[29]

That same month Albert Sharpe and David Wayne were contracted by David Selznick; the pair were appearing in the Broadway smash hit, Finian’s Rainbow.[30] Producer Selznick suspended shooting, pending changes in the script which were handled by Paul Osborn; even with the script revisions, the location scenes shot during the winter were incorporated into the final version of Jennie.[31]

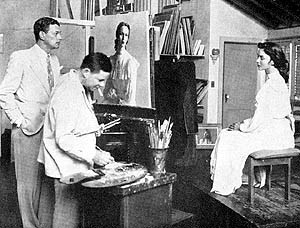

The central part of the story is the portrait in the Portrait of Jennie. David Selznick contacted Robert Brackman and invited him to Hollywood for the task at hand, of which Brackman refused, not wanting to leave his some eighty students, who during the summer lived and worked with him for the season, in Noank, Connecticut.[32] So, Joseph Cotton and Jennifer Jones packed up and traveled to the New London, Connecticut area, staying at the Griswold Hotel and Country Club, (which was situated, roughly eight miles to the west of Brackman’s home-studio-school) at Eastern Point.[33] This art-school that Brackman ran, literally out of his home, was the first incarnation of what would become his Madison Art School, which he opened in 1957, just over thirty-miles west, down the coast from his home.[34]

Some reports have the fifteen sittings (fifteen was typical for Brackman) for Ms. Jones for her portrait that would be immortalized in the Jennie production, as being in the winter of 1947,[35] others no time frame is made reference to at all. But it was in late May of 1947[36] that Jennifer Jones sat for the first time for the famed portrait artist Robert Brackman. Her last day sitting for Brackman was in June, just fifteen days later; leaving Connecticut on June 12.[37] While Brackman may have been demanding to Selznick and troupe his time with Jennifer Jones clearly made a lasting impression, for he often recounted the stories of his sessions with Ms. Jones to his students.[38]

All points of the process of the painting were filmed for the movie, including the Technicolor sequence for the completed work. Joseph Cotton simply observed Brackman (on the few times he was allowed to visit a sitting), never picking up the brush, but putting to memory the style and habits of Brackman.[39] When Cotton attempted to imitate Brackman’s odd stance when wanting a more distant view, the on-set art consultant said “No, no, no, please, please-no artist was ever guilty of such overacting.” The decision of director William Dieterle followed the recommendation of the technical advisor and as Cotten humorously related in his autobiography, “it is nature that copies art, not the other way around.”[40]

Ethel Barrymore arrived in New York, for Portrait of Jennie filming on June 16, 1947.[41] The Jennie unit, worked at the Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park, in New Jersey, then on to Oldwick, NJ, for the picnic scenes and Fulton Fish Market and Central Park back in NYC.[42] Just passed the middle of July the Jennie project was faced with still another month of filming scheduled, this to be done in Hollywood.[43]

The Portrait Delays:

The project saw more delays for various reasons; cinematographer Joseph August passed away on September 25, 1947 of a heart attack. He was photographing scenes at the RKO Pathé studio; August left the set and went to the production office and complained about the heat and fell to floor.[44] Then Selznick decided to wait for new sound equipment from Western Electric;[45] no doubt for the hurricane sequence.

The Finishing Touches and Signature for the Portrait:

Executive (assistant) producer Cecil Barker supervised two camera crews in Florida and Louisiana as they shot over four-thousand feet of film during Hurricane George (more often referred to as the Fort Lauderdale Hurricane) that hit Fort Lauderdale, Florida and into Louisiana, southeast of New Orleans.[46]

The projected opening date for Portrait of Jennie was originally April of 1948,[47] and one report had the film ready to be previewed, at the Selznick Releasing Organization [48] sales event, which was scheduled for January 8-10, 1948, at the Hotel Ambassador in Los Angeles.[49] By February of 48, the date of release for Jennie was no longer solid; now just listed as following the opening of, The Paradine Case.[50] One month later Selznick said he was willing to hold back Portrait of Jennie for the grand opening of the Victoria Theater (under a new name) on Broadway, if the deal went through, which it did not.[51]

In June of 1948, Selznick added ten more days of filming to the project; Cecil Barker, Selznick’s assistant stayed in New York to oversee the background shots ordered by his boss.[52] In September, the release date for Jennie was moved to the first quarter of 1949.[53]

It was reported that editing was completed by the middle of July, 1948;[54] but to say that cutting was over was not accurate. Editing continued into August, and the preparation was under wraps as usual.[55] Selznick was still mixing colors and attempting to improve the looks of the picture, edits were made and new dubbing was added as late as February, 1949.[56] This then is the actual final version of the film we have grown accustomed to; regardless of how minute the changes may have been by Selznick, still what was seen before these last tinkers is not what we see today.

Dimitri Tiomkin was selected to compose the music for Jennie, in August of 1948; at that point the projected opening date was early October.[57]

Finally, in October of 1948, it was admitted by Selznick and company that Portrait of Jennie would be released just under the Academy Award consideration dead-line,[58] which usually meant around Christmas. Sometime in November, for sure before Thanksgiving, Dimitri Tiomkin finished the recording of the score for Portrait of Jennie.[59]

Figures on the Canvas with No Names:

Frank Beetson Jr., who had worked on, Duel in the Sun and The Paradine Case, for Selznick, filled the position of wardrobe director again.[60]

Veteran makeup man Mel Berns (Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons) acted as the makeup Director for Jennie.[61]

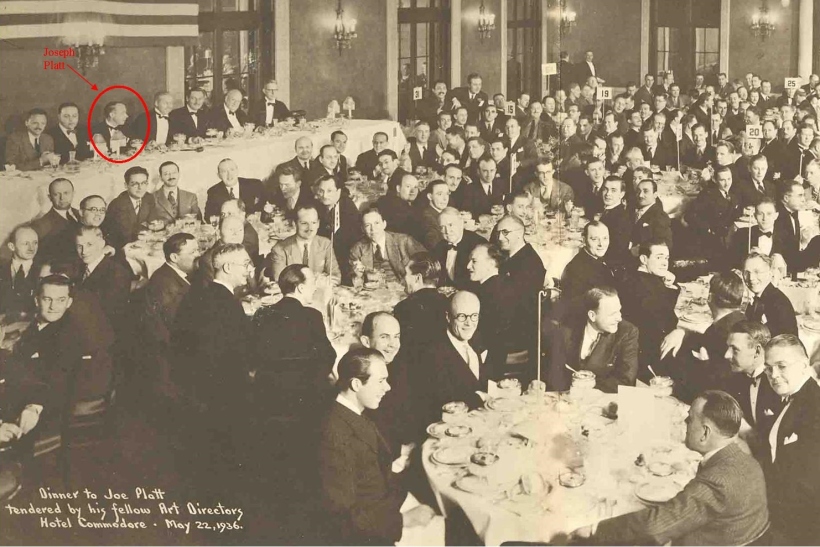

Joseph Platt, a former president of the Art Directors Club[62] and a two-time scenic designer on Broadway,[63] who had done designs for, Gone with the Wind, Rebecca and The Paradine Case was the art director for the project.[64]

Clem Beauchamp who was the production manager of over twenty-five films (Champion, Cyrano de Bergerac, High Noon and The Defiant Ones) was the unit manager for Jennie.

Morris Rosen, who is listed as a grip for Portrait of Jennie on the Internet Movie Data Base, actually was the head grip for the production;[65] Rosen saw work as a grip on more than forty movies, including: Duel in the Sun, Rope, The Men and On the Beach.

One name that is absent from the cast is that of Joseph Buloff;[66] obviously Buloff did not make an appearance in Jennie, yet he was announced as a member of the Jennie group of performers. At the same time as the cast members (including Buloff) of Jennie traveled from New York to California, Buloff was signed for a part in, To the Victor, a Warner Brothers production.[67] What part was Buloff to play in Jennie? That we may never know.

By the first week of October, 1947, Paul Eagler was named to replace cinematographer Joseph August who died of a heart attack on September 25.[68] Eagler began in Hollywood in the silent era, in 1917 and his last film was released in 1960; along the way working on, Dead End, The Hurricane, Foreign Correspondent, and The Killing.

Jules Bricken supervised Portrait of Jennie while the project was in New York.[69] Mr. Bricken only had one other production in which he was a manager that was the 1948 release, Close-Up; he had two movies as producer, Drango, 1957 and The Train in 1964. The most productive portion of his career was in television as a director and producer. Bricken had a thirty-six year stint in the entertainment industry.

Canvas Curiosities:

In the last days of shooting extra scenes for Portrait of Jennie, in Central Park, the very last scene was in the sheep meadow; fifteen sheep were hired from a Hicksville farm. Director William Dieterle also contracted for a sheep dog, the scene cost Selznick $800.00 in overtime, resulting from a sheep stampede through Central Park, pursuing the sheep dog. The dog’s owner apologized for the animal’s behavior saying “the dog was frightened. He’s never seen sheep before.” [70]

During the ice-skating scene in Central Park, Jennifer Jones ruined the original take because of her being blue. She in fact began turning blue in the 19-degree weather in February of 1947. This particular scene and several other close-ups eventually were filmed in an ice-house in Los Angeles, where three-hundred-pound blocks of ice, ground down, substituted for snow.[71]

Joseph Cotten recounted the filming of one love scene which was shot at 4:00 A.M. on the Brooklyn Bridge; “It was a bit difficult to keep the scene serious and romantic when a fragrant garbage scow floated by.”[72] So much for realism.

Harmonica genius Alan Schackner, taught Joseph Cotton to play the mouth-harp for his role as Eben Adams for Portrait of Jennie.[73]

Portrait of Jennie won the Gold Medal Award from the American Schools and Colleges Association for Mr. Selznick for 1949.[74]

Morris Rosen the head grip for Selznick on Portrait of Jennie was the inventor of the All-angle-trackless-dolly; not satisfied, Rosen made improvements on his own work. The mount was hand driven, could move forward, sideways, backward in one operation; he had developed and used what would become known as “Rosie’s Dolly” for the first time on Alfred Hitchcock’s, The Paradine Case, another David Selznick production.[75]

While Jennifer Jones was staying at the Griswold Hotel and Country Club, in Eastern Point, Connecticut, she found that a convention of Connecticut dentists was in residence at the hotel as well. The dentists’ awards committee informed Ms. Jones that she had been selected as, “The Girl Who Brings Out the Enamel in Men.”[76]

The special equipment that needed to be installed into theaters like the Rivoli in New York and the Garrick in Chicago for the full Portrait of Jennie experience, which included near deafening sound effects, took two years and three million dollars to develop and produce. As to the sound-effects, some found it over-the-top, as with New York Times film-critic, Bosley Crowther when he wrote on March 30, 1949, referring to the sequence as “a howling hurricane that will blast you out of your seat.” Producer David Selznick wanted to show the film in these venues for indefinite periods, which for Chicago was prohibited to protect small neighborhood theaters. Selznick took the matter before Federal Judge Michael Igoe and got authorization for the extended runs with open end dates for Chicago.[77]

Publicity and Promotions of the Portrait:

No manner of publicity went unused to promote Portrait of Jennie, from greeting cards and cast pictures;[78] a song of the same name recorded by Nat King Cole was heard on radio and for sale at the local record store.[79]

A new device was used for, Portrait of Jennie, called a “Telelight,” working like a teletype machine; it would light up and promote Jennie with interesting information about the movie. The locations chosen for the program were in Hollywood and Los Angeles at Laundromats.[80]

Sam Goldwyn leased six-hundred billboards in and around Los Angeles, simultaneously promoting his film, Enchanted, for the Academy Awards, and preempting others from advertising on the boards, which left Selznick’s Jennie (and other Academy hopefuls) with little or no traffic advertising for Academy voters.[81]

Jennie was aggressively advertised on radio and television with cross promotions galore. A prize on ABC’s, Stop the Music, was a $1,500.00 pearl necklace with a diamond clasp, matching the one worn by Jennifer Jones in the movie.

The Queen for a Day, radio program originated their Christmas Eve program from the Carthay Circle Theatre in Hollywood, this on the eve of the official opening of Portrait of Jennie at that theater.[82]

Even real artistic talent was not left alone with Portrait of Jennie advertising, for in forty-three Los Angeles high-schools art students were having a, Portrait of Jennie, portrait contest.[83] No report as to the winner.

Jennie publicist Paul MacNamara, thought of using a gigantic (100 feet by 100 feet) reproduction of the portrait from the movie in tow by an airplane through the skies of Southern California.[84] I wish I could verify if MacNamara followed through on his idea, but sad to say I have not.

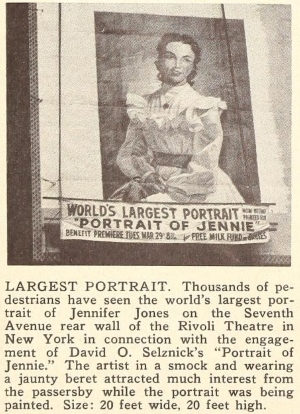

A 20 by 20 foot replica was painted on the Seventh Avenue rear wall of the Rivoli Theatre in New York; the hand painted reproduction was seen by thousands of even the most casual of those walking by. The artist (unnamed) attended his daily work in smock and beret which attracted the more attention.[85]

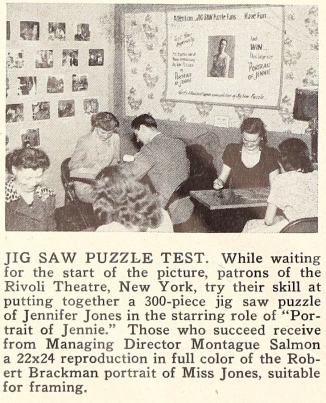

The Rivoli Theatre in New York, offered an additional promotion, this was a jig saw puzzle contest. While waiting for the start of Jennie, patrons could try to assemble a three-hundred-piece puzzle of Jennie, those who finished received a 22×24 reproduction in full color of the Robert Brackman portrait of Jennifer Jones.[86]

On Mother’s Day, 1949, another Rivoli Theatre promotion offered free admission for a mother brought by one of her children; the first five hundred mothers received a flower from New York florist Warendorff. The next five hundred got the suitable for framing 22×24 replica of the Portrait of Jennie by Robert Brackman.[87]

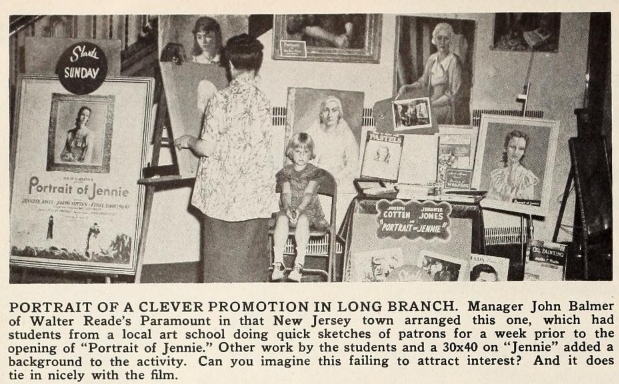

At the Walter Reade’s Paramount Theatre in Long Branch, New Jersey, manager John Balmer arranged for students from a local art school to do quick sketches of customers, this done the week leading up to the opening of Portrait of Jennie at the theater. Students also produced a 30×40 Jennie.[88]

Leave it to some inventive showman and things will always be improved upon, and so was the case with showings of, Portrait of Jennie, in New Jersey. The manager of the Walter Reade’s Community Theatre in Morristown expanded the impact of the storm scene in Jennie. Each showing was accompanied by three flash bulbs for photos, which were placed in the floodlights located at the base of the stage. When lightning flashed on screen, the booth operator hit the switch setting off the flash bulbs. The stunt was well received and was used for each viewing. [89]

Fashion of the Portrait:

Before Portrait of Jennie was seen in a theater, a special time was planned by David Selznick at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for Monday afternoon on October 11, 1948. This would be the unveiling of Robert Brackman’s portrait of Jennifer Jones as Jennie, with the work spending time in the Met gallery. A fashion show was also scheduled for the event; new creations by some of New York’s foremost designers (Trigere, Vera Maxwell, Philip Mangone, John Frederics, and Toni Owens) were seen at the show as well as the original costumes worn by Jones in the Portrait of Jennie.[90]

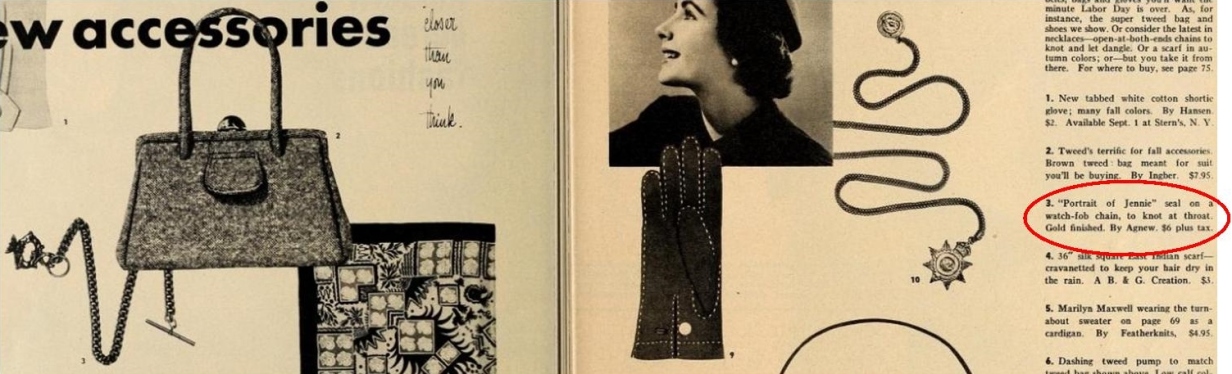

Jewelry was designed with the Portrait of Jennie seal, by Agnew, for sale at the Peck and Peck shops.[91] This trinket design ushered Jennie, a perfectly fictional character from the pages of a book and her subsequent adaptation into moving-pictures, into the real world.

J. C. Penny hosted a “fashion carnival” in connection with the release of Jennie in Salt Lake City; the fashion show was staged at the Uptown Theatre.[92]

A hat was made, inspired by the title character of the film, The Jennie Beret, created by Mallory and produced in eleven colors.[93] This chapeau really topped things off.

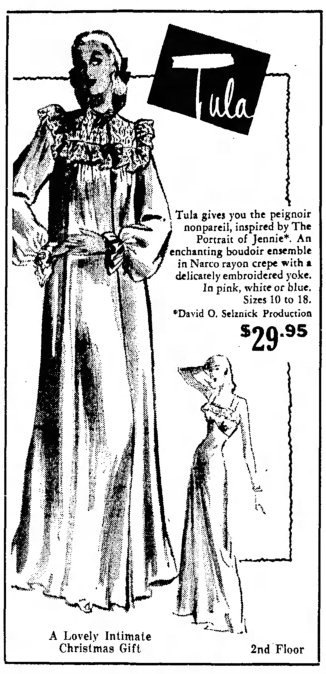

Tula designed a peignoir nonpareil, inspired by the, Portrait of Jennie. The enchanting boudoir ensemble, as it was described was manufactured in Narco rayon crepe, delicate embroidery at the yoke, available in pink, white or blue, sizes 10 to 18; the set was offered for Christmas shopping 1948, with retail prices ranging from $29.95 to $32.50.[94]

Portrait of Jennie is available on DVD (at a hefty price) but has not yet been released on Blu-Ray.

By C. S. Williams

[1] Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) December 25, 1948

Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) December 18, 1948

Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) December 26, 1948

[2] Times (San Mateo, California) November 18, 1948

Long Beach Independent (Long Beach, California) November 30, 1948

Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah) December 1, 1948

[3] Santa Cruz Sentinel (Santa Cruz, California) November 18, 1948

[4] Long Beach Independent (Long Beach, California) November 27, 1948

[5] Paramount Pictures Distributing Corporation, Loew’s Incorporated, RKO Radio Pictures, Universal Pictures,

Universal Film Exchanges, United Artists, Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation, National Theaters

Corporation, National Theaters Amusement, Fox West Coast Theatres Corporation

[6] Bakersfield Californian (Bakersfield, California) November 24, 1948

Post-Standard (Syracuse, New York) December 21, 1948

Variety, December 24, 1948

United States Court of Appeals For the Ninth Circuit, February 27, 1957

[7] Showmen’s Trade Review, January 1, 1949

[8] Showmen’s Trade Review, January 15, 1949

[9] Showmen’s Trade Review, January 1, 1949

[10] Post Standard (Syracuse, New York, April 30, 1949

Portland Press (Portland, Maine) May 4, 1949

Salt Lake City Tribune ( Salt Lake City, Utah) June 24, 1949

[11] Gazette and Daily (York, Pennsylvania) December 24, 1949

[12] Showmen’s Trade Review, March 19, 1949

[13] Kansas City Star (Kansas City, Missouri) March 24, 1949

[14] Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) March 28, 1949

[15] Motion Picture News, May 17, 1949

[16] Salt Lake City Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah) April 13, 1949

[17] Motion Picture Daily, April 20, 1949

[18] Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) April 19, 1949

[19] Film Daily, December 28, 1943

[20] Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) December 27, 1943

[21] Film Daily, January 14, 1944

[22] Showmen’s Trade Review, February 5, 1944

[23] Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah) January 20, 1944

[24] Film Daily, July 21, 1947

[25] Film Daily, March 5, 1947

Film Daily, June 20, 1947

[26] Film Daily, June 17, 1947

[27] Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) March 2, 1947

[28] Film Daily, April 25, 1947

[29] Film Daily, July 11, 1947

[30] Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) April 9, 1947

[31] Film Daily, June 20, 1947

[32] The Day (New London, Connecticut) December 18, 1948

[33] The Day (New London, Conn) June 12, 1972

[34] Los Angeles County Museum of Art

[35] Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, Texas) August 17, 1949

[36] The Day (New London, Conn) June 12, 1972

Either May 28 or 29 was her first sitting

[37]The Day (New London, Conn) June 12, 1972

Either June 11 or 12 was her last sitting

[39] The Day (New London, Connecticut) December 18, 1948

Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, Texas) August 17, 1949

Vanity Will Get You Somewhere: An Autobiography, by Joseph Cotton, published by Mercury House, 1987

And digitized by toExcel Press, 2010

[40] Vanity Will Get You Somewhere: An Autobiography, by Joseph Cotton, published by Mercury House, 1987

And digitized by toExcel Press, 2010

[41] Film Daily, June 17, 1947

[42] Showmen’s Trade Review, July 12, 1947

[43] Film Daily, July 18, 1947

[44] Showmen’s Trade Review, October 4, 1947

[45] Showmen’s Trade Review, October 18, 1947

[46] Showmen’s Trade Review, October 4, 1947

[47] Film Daily, October 22; November 17, 1947

[48] Film Daily, December 8, 1947

[49] Film Daily, December 8, 1947

[50] Film Daily, February 16, 1948

[51] Film Daily, March 5, 1948

[52] Film Daily, June 23, 1948

[53] Film Daily, September 20, 1948

[54] Showmen’s Trade Review, July 24, 1948

[55] Film Bulletin, August 30, 1948

[56] Cumberland Evening Times (Cumberland, Maryland) February 3, 1949

[57] Showmen’s Trade Review, August 7, 1948

[58] Film Bulletin, October 11, 1948

[59] Showmen’s Trade Review, November 27, 1948

[60] Film Daily, September 10, 1947

[61] Film Daily, September 10, 1947

[62] Art Directors Club Annual 90, published by AVA Publishing, 2011, page 391

[63] Internet Broadway Data Base

[64] Film Daily, September 10, 1947

[65] Film Daily, September 10, 1947

[66] Film Daily, July 21, 1947

Film Daily, September 5, 1947

Film Daily, September 10, 1947

Modern Screen, May, September, 1949

[67] Film Daily, September 4, 1947

[68] Showmen’s Trade Review, October 4, 1947

[69] Film Daily, March 1, 1948

[70] Times (San Mateo, California) July 26, 1948

[71] Record-Argus (Greenville, Pennsylvania) September 22, 1947

[72] Record-Argus (Greenville, Pennsylvania) September 22, 1947

[73] Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) February 19, 1949

[74] Motion Picture Daily, April 26, 1949

[75] Film Daily, September 5, 1947

[76] Amarillo Daily News (Amarillo, Texas) July 4, 1947

[77] Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1949

[78] Miami Daily News-Record (Miami, Oklahoma) January 13, 1949

[79] Modern Screen, May, 1949

[80] Miami Daily News-Record (Miami, Oklahoma) December 28, 1948

[81] Salt Lake City Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah) November 10, 1948

[82] Showmen’s Trade Review, December 25, 1948

[83] Miami Daily News-Record (Miami, Oklahoma) January 13, 1949

[84] Miami Daily News-Record (Miami, Oklahoma) January 13, 1949

[85] Showmen’s Trade Review, April 2, 1949

[86] Showmen’s Trade Review, May 7, 1949

[87] Showmen’s Trade Review, May 7, 1949

[88] Showmen’s Trade Review, July 23, 1949

[89] Showmen’s Trade Review, July 16, 1949

[90] Amarillo Daily News (Amarillo, Texas) September 29, 1948

Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) October 3, 1948

[91] Modern Screen, September, 1949

[92] Miami Daily News-Record (Miami, Oklahoma) January 13, 1949

Showmen’s Trade Review, June 11, 1949

[93] Delta Democrat-Times (Greenville, Mississippi) September 7, 1947

[94] Bakersfield Californian (Bakersfield, California) November 16, 1948