Author’s Note:

I find it surprising that no extensive description has been written about Mr. Otis Turner; especially as we consider his important position in Hollywood history. To be sure, the name of Otis Turner has been seen in numerous books about the early days of film or personages of that era. But, those mentions are little more than passing glances at man that deserves much more. While his appearances in books, articles and blogs are many, yet, they are short by nature; often only a few lines or a couple of pages in total within a particular volume. It is my great pleasure to set down, although not far-reaching, at least some account, bringing into context, the personal side, the talent and the experience of that famed film-director Otis Turner.

The Rough Sketch:

Willard Otis (both names were seen as follows: Williard; Ottis) Turner was born on November 29, 1862, in Fairfield, Indiana, to James Turner, who when not practicing medicine owned and operated a saw-mill. His mother Elizabeth took care of the family and a sometimes provided additional income by working as a housekeeper. Fairfield sat toward the northeast corner of Franklin County, and was about fifty miles to the northwest of Cincinnati, Ohio, and eighty-five miles southeast of Indianapolis, Indiana; the community was less than fifteen miles west of the Ohio State line. The Turner family did not remain in Fairfield for the long term, they moved to Indianapolis by 1870. When Otis was fifteen his parents had a second child, Ben, in January of 1878. In 1880, one could say, that Otis took his first professional position in live performance, as a telephone operator in Indianapolis. . In 1881, Otis struck out on his own, moving into his own place, albeit still in Indianapolis, near his parents.

Otis Turner is credited with several firsts in the film industry, the first wild animal film (Hunting Big Game in Africa), the first war picture (Stormy “Stirring” Days in Old Virginia), the first feature film made in America (Spirit of ’76) the first western (The Cowboy Millionaire), the first three-reel movie, which was the, Coming of Columbus, and the first president of the Motion Picture Directors’ Association, serving two years in that capacity.[1]

Much of what made Otis Turner a popular director with all of those involved in the film industry was his kindness. He often was a father to those actors around him, addressing them as such. He was a tolerate man, dealing with mistakes and artistic temperament with a good nature that was unfailing; not allowing their behavior to change or disturb his mood. He was always available to talk and not just to those that were currently filming with him, but to anyone at the Universal studios. Often when not busy with actual filming or preparation for a scene, Turner could be found listening uncomplainingly to the troubles of one of his actors or his children as he referred to them. Otis Turner conducted himself in a gentle, quiet voice, a demeanor devoid of harshness in his many dealings with others.[2]

Turner was a man besieged by arthritis, causing him to hunch-up, he was five-and-a-half-feet tall, broad chinned, round faced with a dark complexion, his pug nose and high forehead, set off by gray-black hair. Known (even by the early 19-teens) as the “Dean of Directors,” if an actor was on Turner’s list, they were considered “in,” for he was the king bee of the Universal lot.[3] Everyone that worked with Turner referred to him as “Daddy” or “the Governor,” and to commemorate the 25th anniversary of his passing, it was noted that he was known as the father of the motion picture industry in Hollywood; what volumes these remembrances speak of Turner’s contribution to those all important formative years in the moving pictures.[4]

Otis Turner worked with the who’s who of the early film community both in Chicago and in California; although an experienced stage-manager he found that he had to unlearn many things when beginning in motion pictures. Changing from the repose of the stage to the rapid expressions and gestures needed to communicate the character’s emotions, in a one or two reel movie.[5]

Turner’s Turns:

Turner’s genesis was on stage, in touring companies, and stock theater; his name appearing in print dozens of times across our nation, prior to his movie days. At the age of eighteen he went before the footlights and when he was twenty-three, Turner married actress Estella C. French Dale (sometimes appearing together on stage; she used her family name, Dale, for her stage work[6]) in 1885; Estella had a daughter, Dolores, from a previous marriage. Estella would not only be a loving companion but a professional intimate for Otis, acting as a sounding-board for stories of future productions he was to be involved in.[7] 1885 brought the partnership of Turner and Fred Julian, the two organizing a summer repertoire company that played the resort theaters on the New England coast. Turner-Julian would continue this summer practice through the late 1890’s.[8]

By 1887, before his twenty-fifth birthday, Turner was already a renowned comedic actor.[9] On stage he was well known for “dialect acting,” specializing (he started with the different accents around, 1893) in those parts requiring the brogue of the Irish, a cockney accent, a black man from the south. Of his own account after spending a year or more in the “role” he would slip into that particular dialect during his own personal time.[10] His major stage triumphs were in, Shenandoah, which he toured in for three years, and he spent another three years with the touring company of, In Old Kentucky;[11] with, The College Widow, he toured from 1905 through early 1908.

Autumn of 1898 through the spring of 1901 saw Otis Turner in the role of Sergeant Barket in, Shenandoah; this truly, his breakout role, he receiving splendid reviews for his portrayal.[12] In the summer of 1900, Mr. Turner supplemented his bank-roll by acting as a major in a circus; at the circus he was the head of a troupe of twenty-five performers.[13] By the start of the next theatrical season in September of 1900, Turner was back as Barket in Shenandoah.[14]

In December of 1901, Turner began what would be his only appearance on Broadway, in the Henry Miller comedy, D’Arcy of the Guards, in the part of the servant, Sambo, with that cockney flair;[15] the play was short-lived ending in February of 1902. D’Arcy was for Turner a near one year experience, beginning with the play’s world premiere in San Francisco on June 10, 1901 at the Columbia Theatre. D’Arcy ended its San Francisco run on June 24; the D’Arcy troupe played two nights in Vancouver, August 7-8. It was not until autumn that any consecutive dates and cities were achieved for the company; starting with performances in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in Scranton and Harrisburg, PA…[16] These dates were followed by scattered presentations in November in, Lebanon and Allentown, Pennsylvania.[17] At the Savoy Theatre on December 16, 1901, D’Arcy was welcomed on the Great White Way and although the play ended its Broadway run on Sunday, February 2, 1902, it was not because of ticket sales, but instead because Henry Miller had a previous contract for June of 1902 on the west coast.[18] In the meantime, post Broadway tour dates were played in Philadelphia, Chicago, Brooklyn, Washington, D. C. and as well, back in New York City, this time at the Grand Opera House.[19] All of this prior to taking up an advertised fifteen weeks (actually it turned out to be just twelve weeks) of stock-work at the Columbia Theatre in San Francisco, commencing on June 9, of 1902;[20] the company offered both classic and contemporary productions. This great tour and Broadway run had all begun one year before on June 10, 1901, at the same City by the Bay theater; now June 9, 1902 saw the Henry Miller Company in Trelawny of the Wells; Mr. Turner still in play so to say.[21]

Turner went his separate way (from the Miller Company) at some point in the middle of July, heading back to New York,[22] and it is a good thing that he did for beginning in August of 1902, Turner landed with the, In Old Kentucky, tour (beginning in late August, 1902, in Saint Paul, Minnesota[23]) which role would last for three years; he portraying, Uncle Neb. Turner also pulled the duty of stage-manager for the, In Old Kentucky, troupe.[24]

From the early summer of 1905 through February of 1908, Turner and his wife Estella (she joined the company in September of 1906) were part of, the Henry W. Savage tour production of, The College Widow; Otis appeared as the town marshal, Daniel Tibbetts and Estella was featured as the professional chaperone, Mrs. Daizelle.

Daddy Turner:

By spring of 1908, Turner was directing for the Selig Polyscope Company, with, Rip Van Winkle being the first verifiable title of his film making résumé. This fits perfectly, with the chronological evidence that, The College Widow, played in Chicago, at the Studebaker Theatre, beginning on February 16 of 1908 and ending the run on Saturday, February 29. Turner began work at the Selig studios in Chicago on the Rip Van Winkle production, which was released in May of 1908.[25]

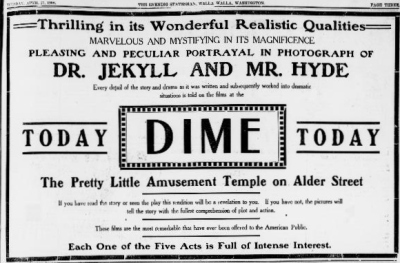

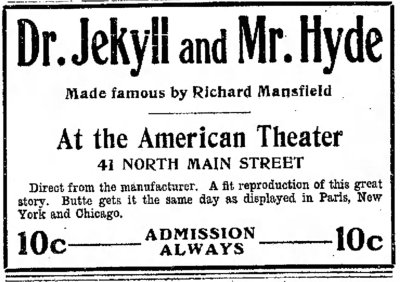

Some have put forth the conjecture that Turner directed, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which most have thought it opened on March 7, 1908,[26] but instead, its initial bow was on Tuesday, February 25, 1908; other dates prior to March 7, also had the premiere of the film.[27] Below is one of the rare display ads promoting the movie.

The one-thousand-thirty-five foot one-reeler was colored (tinted);[28] this alone would have impressed the movie-goer, then adding the subject matter, brought many nickels and dimes to exhibitors. Take notice of the international release publicity used to induce movie patrons.[29]

It seems unrealistic that Turner had time to direct Jekyll and Hyde, after working nights and some days through the end of February with his role as the marshal of the town in, The College Widow. I will not say that it was impossible; just that is was not likely.

In early December of 1908 with the production of the military action-drama, entitled, Stirring Days in Old Virginia,[30] Otis Turner took a Selig Polyscope company of actors and actresses, along with cinematographer J. A. Crosby to Leavenworth, Kansas to film the actioner. Those soldiers stationed at Fort Leavenworth were involved in the making of the movie. The township and Colonel Loughborough, the commander at the Fort, believed that the film would be an advertisement for the community and an enlistment tool for the army.[31] Otis Turner directed, Brother Against Brother, which had an April, 1909 opening (filming took place in December of 1908 and January of 1909), the film starred Fred Herzog; Herzog was at the time, the leading man for Selig.[32] Turner was already considered an elderly man (at the time of filming of Brother Against Brother) by the reporter for, The Inter Ocean (a Chicago newspaper); he had just turned forty-seven.[33]

In March of 1910, Selig sent Otis Turner west, with Indians, cowboys, cowgirls, rough riders, bucking broncos and steers, cavalry horses and the accompanying equipment, hospital and commissary departments were also sent along. It was on this trip that Turner chose rodeo star and horse expert, Tom Mix to help with the horses and cattle for the upcoming production of, Ranch Life in the Great Southwest. In July of 1910, Mix would also assist Turner with the, Lost in the Soudan, project, which filmed at Dune Park, east of Gary, Indiana, by being wrangler to the camels.[34]

Turner and family moved from Chicago (at that time the hub of the movie industry) in the summer of, 1912; Otis had left Selig and became head of IMP (Independent Moving Pictures Company of America), in early 1912 (O’Brien’s Busy Day, was his initial offering for IMP, opening near the first of February), then he was quickly appointed as director of the new Universal venture in Hollywood, 101-Bison.[35] The first 101-Bison project for Turner was, Hunted Down; that movie opened in late October of 1912, and in March of 1913 Turner vacated his position at 101-Bison and went to the Rex Company.[36] The Turner family took up residence in Los Angeles (San Pedro), in a bungalow at 1524 Formosa Avenue; Otis still considered himself an actor, he being listed as such in that city’s directory in 1914.[37]

In 1916 Turner started the Hollywood Decorating Company (painting contractor), out of his home on Formosa Avenue. Not too long after (no later than early 1917), the business moved to 6421 Hollywood Boulevard. In August of 1916 after more than four years at Universal Studios, he accepted an offer from Fox Film Corporation[38] and his first movie for them was the November, 1916 release, The Mediator, starring George Walsh and Juanita Hansen. Turner made a total of nine films for Fox, with his last (his last film overall) The Soul of Satan, which opened in August of 1917.

Otis and Estella Turner moved (circa, late 1916 or early 1917) to a two-story bungalow at 1612 Curson Avenue, in Hollywood, where Otis would spend his final months fighting chronic heart disease.[39] He succumbed to the prolonged physical battle at his home in Hollywood, on Thursday, March 28, 1918, and was buried two days later on Saturday, March 30; director, Phillips Smalley and actor J. Warren Kerrigan were among his pall bearers. Turner was an active member of the Masons and at the request of his family his remains were transported from California to Chicago[40] and from there on to his final resting place, at Crown Hill Cemetery, in Indianapolis, Indiana. He was survived by his wife Estella, who had quit acting once Otis began his movie career;[41] she never did return to the stage. The Hollywood Decorating Company was sold to a competitor within six months of Turner’s passing.[42]

Further Turner:

Turner was a playwright, co-authoring, The Old Home Town, with Charles W. Doty in 1905. In 1906 he co-wrote three works: A Yankee Doodle Princess, with Arthur Gillespie; New Harmony: a Musical Play in Three Acts, with the score by Horatio N. Peabody, lyrics by Arthur Gillespie, with Turner and Gillespie providing the book; Turner and Charles W. Doty, wrote, The Red Light Mission: a Melodrama in Four Acts and Eight Scenes. Turner penned, The Rival Dramatists or: Cock-A-Doodle-Doo!, in 1910; a one act playlet about the reigning French dramatic craze.

Confused About Turner:

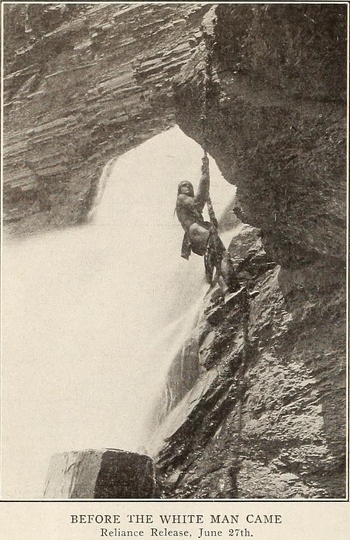

The June, 1912 release, Before the White Man Came, starring Gertrude Robinson, was supposedly directed by Otis Turner (seen on the Internet Movie Data Base), this attribution is wrong. The June, 1912, Before the White Man Came, release was a Reliance Film Company production, at which time Turner was working with 101-Bison. 101-Bison did release a film of the same title in December of 1912; that Bison project then, is the Turner version and not the Reliance flick. The Reliance film did not list the number of reels, but the Bison, Before the White Man Came, was advertised as two-reels.[43] More confusion is added to this by the fact that Wallace Reid co-starred in both versions (and co-starred with his wife Dorothy Davenport in the remake of the Reliance project in 1913: A Hopi Legend); he portrayed Wathuma, The Leopard (the romance of Meene-O-Wa “Yellow Rose,” the fairest maiden of the Utes and Wahtuma the man who loves her[44]) in the Reliance version[45] and Willow (the Apache romance legend of Willow and the Sunbeam[46]) in the 101-Bison edition.[47] Wallace Reid had left Vitagraph for Reliance in the spring of 1912 and soon moved on to 101-Bison;[48] thereby explaining how he appeared in both versions of, Before the White Man Came, with different companies.

The movie listed on the Internet Movie Data Base’s history for Otis Turner, as, Get the Boy, 1916, is an AKA, it is, Youth of Fortune; that being verified by the Moving Picture World on May 13, 1916, in saying the same. Youth of Fortune, was a Universal film; some of which was directed by Harry Carter.[49]

Turner is Missing:

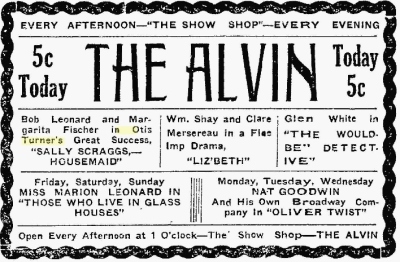

At least seven (probably many more) films are missing from Otis Turner’s work history on IMDB, they are: The Spirit of ’76, 1908, Brother Against Brother, 1909, Hunting Big Game in Africa, 1909, The Coming of Columbus, 1912, each of these four were Selig Polyscope productions, Sally Scraggs: Housemaid, The Diamond Makers, each a Rex Motion Picture Company project released in 1913 (both attributed to Robert Z. Leonard as director, which would make him assistant to Turner), and Her Temptation, 1917 made for Fox.[50]

Continuing on the subject of missing credits, Mr. Turner is listed as an actor on Internet Movie Data Base just once, that in 1908, in Damon and Pythias; a film which he also wrote and directed. Yet, with a more thorough search, we find that Turner appeared in, Won in the Clouds, 1914, another movie that he directed and wrote; he portrayed the banker. Turner said that he had to have someone to play a banker for Clouds; he could find no one, so he decided to play the part himself.[51]

Otis Turner, a man that was an integral part of the formation of Hollywood, a leader and a trail-blazer in the means and habits of movie-making, offering a solid foundation for generations of professionals to build upon; for directors to emulate and actors to wish for an understanding ear in that all important director’s chair. Unfortunately for us, we will probably never know the emotional impact from his cinematic expertise, seeing that virtually nothing of his work is extant.

By C. S. Williams

[1] Motography, May, 1912

Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual, Published by Motion Picture News, 1916

Motion Picture News, April 20, 1918

[2] Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana) May 17, 1914

[3] The Parade’s Gone By, by Kevin Brownlow, Published by University of California Press, 1968, page 46

[4] Wallace Reid: The Life and Death of a Hollywood Idol, by E. J. Fleming, published by McFarland & Company, Inc.,

2007, pages 25, 122,

[5] Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) January 3, 1909

[6] Fitchburg Sentinel (Fitchburg, Massachusetts) January 10, 1903

[7] Motography, December 26, 1914

[8] Indianapolis News (Indianapolis, Indiana) September 15, 1898

[9] Fort Worth Daily Gazette (Forth Worth, Texas) October 31, 1887

Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual, Published by Motion Picture News, 1916

[10] Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) January 29, 1905

[11] Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) January 29, 1905

Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) January 3, 1909

[12] Indianapolis News (Indianapolis, Indiana) September 15, 1898

Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) February 19, 1901

[13] 1900 Federal Census

[14] Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) September 11, 1900

[15] Internet Broadway Data Base; Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) January 29, 1905

[16] Vancouver Daily World (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) August 7, 1901

Scranton Republican (Scranton, Pennsylvania) October 8, 1908

Harrisburg Daily Independent (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) October 11, 1901

[17] Evening Report (Lebanon, Pennsylvania) November 5, 1901

Allentown Leader (Allentown, Pennsylvania) November 5, 1901

[18] Saint Paul Globe (Saint Paul, Minnesota) January 24, 1902

New York Times (New York, New York) January 28; 30; February 2; 3, 1902

San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, California) February 13, 1902

[19] The Times (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) February 18, 1902

Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) March 19, 1902

Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) March 23, 1902

Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) March 30, 1902

Evening Times (Washington, D. C.) April 10, 1902

New York Times (New York, New York) April 27, 1902

[20] Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah) May 18, 1902

[21] San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, California) June 1, 1902

[22] New York Times (New York, New York) July 20, 1902

Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) August 3, 1902

[23] Saint Paul Globe (Saint Paul, Minnesota) August 24, 1902

[24] Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) January 29, 1905

Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) January 3, 1909

[25] Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) July 30, 1905

New York Sun (New York, New York) September 2, 1906

Winnipeg Tribune (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) October 5, 1906

Indianapolis News (Indianapolis, Indiana) September 24, 1907

Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) February 19, 1908

Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) February 15; 29, 1908

Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) January 3, 1909

[26] Moving Picture World, March 7, 1908

[27] Daily News (Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania) February 25, 1908

Mount Carmel Item (Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania) February 25, 1908

Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana) February 27, 1908

Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina) February 28, 1908

[28] Daily News (Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania) February 25, 1908

Mount Carmel Item (Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania) February 25, 1908

[29] Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana) February 27, 1908

[30] if not Stirring Days, then Brother Against Brother, an April, 1909 release..

[31] Leavenworth Times (Leavenworth, Kansas) November 24, 1908

Topeka Daily Capital (Topeka, Kansas) December 3, 1908

Moving Picture World, December 5, 1908

[32] Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) January 3, 1909

[33] Frederick North Shorey: Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) January 3, 1909

[34] The Transformation of Cinema, 1907-1915, Volume 2, Part 2, by Eileen Bowser, published by University of

California Press, 1990, pages 155-156

[35] Motography, August 31; September 14, 28; 1912

[36] San Antonio Light (San Antonio, Texas) March 23, 1913

Motion Picture Story Magazine, May, 1913

[37] Motography, December 26, 1914

[38] Scranton Republican (Scranton, Pennsylvania) August 15, 1916

[39] Wallace Reid: The Life and death of a Hollywood Idol, by E. J. Fleming, published by, McFarland & Company, Inc.,

2007, page 122

[40] Proceeding of the M. W. Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the Jurisdiction of California, 1918, page

210

[41] San Bernardino County Sun (San Bernardino, California) March 29, 1918

Motion Picture News, April 20, 1918

[42] Holly Leaves (Hollywood, California) September 28, 1918

[43] These few advertisements are for the, June, 1912 release of Before the White Man Came, a Reliance picture:

Monroe News-Star (Monroe, Louisiana) July 12, 1912

The Eagle (Bryan, Texas) July 19, 1912

Seymour Daily Republican (Seymour, Indiana) August 8, 1912

Wichita Daily Times (Wichita Falls, Texas) December 1, 1912

The following listings show, Before the White Man Came, the two-reel, December, 1912, 101-Bison release:

Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio) December 15, 1912

Allentown Democrat (Allentown, Pennsylvania) December 21, 1912

Oil City derrick (Oil City, Pennsylvania) January 2, 1913

Bonham daily Favorite (Bonham, Texas) January 27, 1913

Lead Daily Call (Lead, South Dakota) February 28, 1913

Daily Notes (Canonsburg, Pennsylvania) March 6, 1913

Coshocton Tribune (Coshocton, Ohio) April 15, 1913

[44] Moving Picture News, June 8, 1912

[45] Moving Picture World, September 28, 1912

[46] Moving Picture News, December 14, 1912

[47] Supplement to The Cinema, March 5, 1913

Motion Picture Magazine, February, 1915

[48] Motion Picture Story Magazine, June; August; October, 1912; January, 1913

[49] Motion Picture News, January 22; February 5; 12, 1916

Moving Picture World, February 5; March 11; May 13, 1916

[50] Frederick Post (Frederick, Maryland) July 31, 1913

Mansfield News (Mansfield, Ohio) September 3, 1913

Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual, Published by Motion Picture News, 1916; 1918

[51] Marion Daily Star (Marion, Ohio) February 1914