Before Fielding went Afield for Lubin:

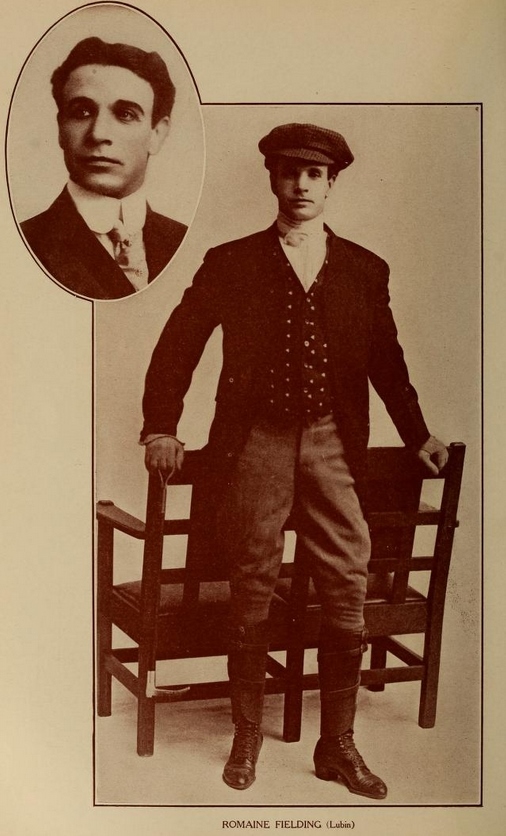

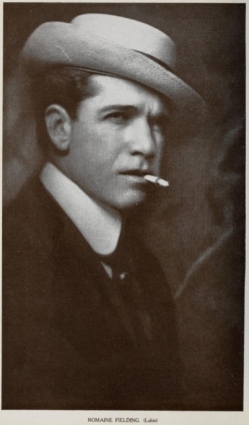

Romaine Fielding appeared in his first Lubin Manufacturing Company movie in late summer of 1911; The Senorita’s Conquest, was released toward the middle of September. 1911 also saw the release of, Love’s Victory, The Mexican, A Romance of the 60’s (according to a letter from an avid fan, to the Dramatic Mirror, Fielding, portrayed Lieutenant Kenney, while Jacking Standing played President Lincoln[1]), The Ranchman’s Daughter, Western Chivalry, The Teamster, and The Soldier’s Return.[2] Of the three Lubin films, starring Fielding, that premiered in January of 1912, two, A Noble Enemy (January 4 release), and, The Blacksmith, which opened on the 11th of January, (some current cast lists do not include Fielding, but according to this reference, he was the male-lead, opposite Ms. Frances Gibson),[3] would have had to have been in the can by the end of ’11. Only, Through the Drifts (which opened in late January),[4] is a candidate for rolling cameras in 1912, and could not have finished production any later than the second week of January, 1912. One more movie to deal with before we move west, The Impostor (a February 3 date for release);[5] it seems to have been filmed in either late 1911 or possibly, as with, Through the Drifts, in, early-to-mid-January, 1912. This ended Fielding’s eastern association with Lubin and offers the beginning for his new assignment in the west. The Lubin Company had (as most film concerns) been producing eastern-made Westerns. Lubin decided to make their Westerns, in the west, for that authenticity, thereby satisfying the ever increasing savvy of the movie goer.

Where and When:

Some sources have this western branch of Lubin arriving in El Paso in December of 1911, but I cannot find any evidence to support this theory; in Joseph P. Eckhardt’s book, The King of the Movies: Film Pioneer Siegmund Lubin, he has the company leaving Philadelphia at the beginning of January.[6] This statement by Eckhardt is supported by a one-paragraph blurb in the Dramatic Mirror saying that the Lubin Western Company had just left; this report came in the fourth week of January, leaving little doubt that the company carrying Fielding did not venture on their journey west until after the first of the year.[7] And if we are to take seriously the contemporaneous witness of a reporter from the Bisbee Daily Review in late February of 1912,[8] then the Lubin Western Branch movie company could not have left Philadelphia any later than the middle of the second week of January; on or about the 10th. Coupling these three sources together gives a firm stance of the departure date-range for the traveling-western-branch of the Lubin Film Company.

Two Years Before the Lubin Mast:

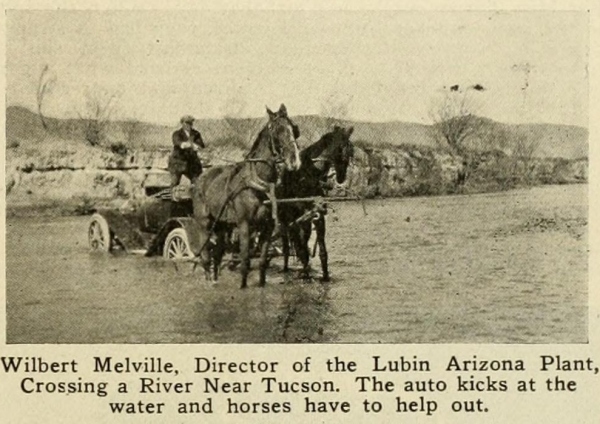

The Southwest Lubin experience began in January of 1912; initially at the helm of the group that would move west, was Wilbert Melville. The traveling film company started in El Paso, Texas, and moving on to four locations in Arizona, Douglas, Tucson, Prescott, and Nogales; then to New Mexico at Silver City, and finally, ending a near two-year trek in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Seven studios in two years, all driven by the search for topographies, buildings, animals and people that would lend realism to the Lubin films of the western genre.

The Lubin Southwestern Branch Film Company, January, 1912, through November, 1913.

Lubin Southwestern Studio One:

El Paso, Texas: January?-February 22, 1912

While in El Paso the Lubin Southwestern Branch Company, staged scenes in the local Mesilla Valley, on the banks of the Rio Grande, and also went northward to the Organ Mountains, filming at the San Augustine Ranch, in New Mexico, which was less than fifteen-miles (as the crow flies) east of Las Cruces, NM and about fifty-miles north of El Paso. It was at the San Augustine Ranch that the Lubin crew, brought to life the stories of cowboys and the western lifestyle.[9]

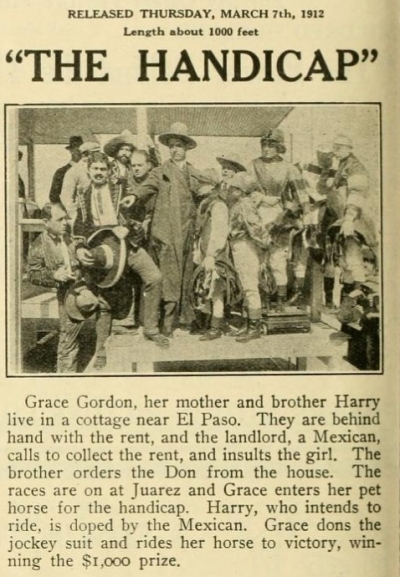

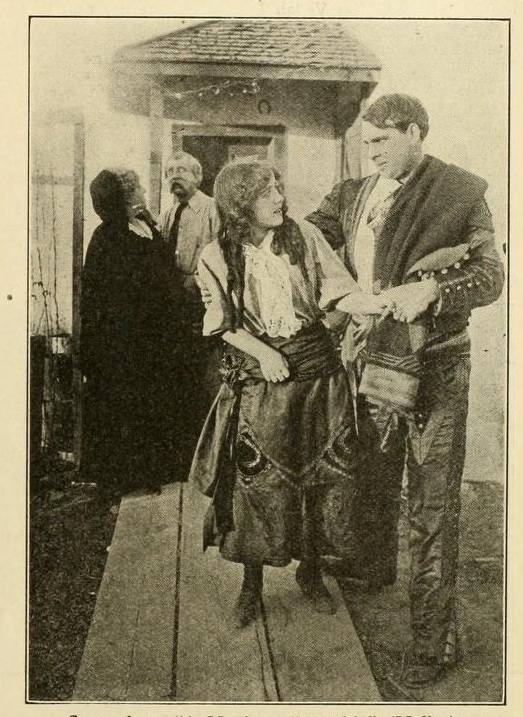

There are two movies to take note of that were made while the Lubin Company was in El Paso. The first being, The Handicap, with a scene filmed at the Juarez, Mexico race track. Great horse race action was the selling point for this short film; and the fact that the jockey was a woman was a novel idea for 1912. The family Gordon (Grace Gordon our heroine), owing back rent, an insulting landlord, a protective brother, a pet horse ridden by a young woman and a $1,000 prize summarizes this scenario.[10]

The second of the El Paso Lubin films that I have mentioned was, A Mexican Courtship. Among the notable scenes taken for the film were at the Juarez Bull Ring; the bull-fight was the drawing card for this film. Extolling the virtues of the favorite pastime of Mexico; A Mexican Courtship, with onscreen deaths of bulls, horses and men, was a romance with a bull-fighting presentation.[11]

Revolution, Permit and Jail:

Manager Wilbert Melville, Romaine Fielding, and the remainder of the Lubin Western stock company were finishing up their sixth-week in El Paso, Texas; abruptly, they would pack and leave, continuing on to Douglas, Arizona. The motive for the exit from El Paso to Douglas, was due to the arrest of three of the Lubin Company (W. J. Wells, P. F. McCafferty and Richard Wangermann), on Tuesday, February 6, 1912, along with thirty-two Mexicans (extras for a large group scene) for vagrancy; [12] this after the movie company had been issued a permit to film (according to Lubin western-branch manager, Wilbert Melville) on the streets of El Paso. A local reporter wrote that a “young riot” started on Oregon Street and that a band of Mexicans, were armed, and heading in the direction of the Mexican Consul. Accounts started coming in throughout the business district, that the Mexican band were marching on Juarez, then that the Maderista soldiers had been routed out of Juarez and were retreating to the foothills of El Paso; others rumored that an armed guard was sent to protect the Mexican consulate.[13] Of course all of the concoctions were based upon those that had seen the Lubin actors and extras parading down Oregon Street on Tuesday morning the 6th of February, in full costume and arrayed with belts, guns, straw hats and visages of anger. Let us not be too quick to criticize the citizens of El Paso of 1912, forming an opinion that they were naïve or ignorant. When these scenes were staged by Wilbert Melville, with his actors involved, hiring more than thirty Mexicans for the battle tableau, was like re-enacting a news item for the denizens of El Paso. Just a few days before the rebel soldiers had agreed to turn Juarez back over to the control of the Mexican Federal authorities, for guaranteed back pay, and transportation to their homes in Mexico upon their discharge from the Mexican military.[14] In fact, the streetcars had just begun running again between El Paso and Juarez and refugees were in the midst of returning.[15] For those residents of El Paso on that morning on February 6, 1912, the rebellion must have to them to appear to have started again. Even though Melville probably did obtain a permit for the filming on Oregon Street, most likely he did not divulge the exact nature of the scenes to the Mayor; leaving the people of El Paso astir, concerned and frightened in many cases at the parade of revolutionaries, regardless that said revolutionaries were doing nothing more than making believe.

The title of the film which had Lubin employees incarcerated and fined was, The Revolutionist (some sources referred to this flick as, The Revolutionists); a contemporary story of the revolution in Mexico in 1912. It was reported that nearly everyone in town saw the scene of the imitation soldiers returning and the actors in portrayal arrested for parading without permission; in April, El Paso, Wigwam Theatre patrons were encouraged to come early or to the late showing to get seats, as they expected sellouts for the 7:30 and 9:30 PM viewings. The battle which in the storyline took place prior to the parade of soldiers, was filmed at the smelter and offered good battle scenes.[16] It was at that point an invitation from the Chamber of Commerce of Douglas arrived and Wilbert Melville the director of this Lubin clan accepted.[17]

Lubin Southwestern Studio Two:

Douglas, Arizona: February 23-March 30, 1912

While arriving on February 23, it was on Saturday, the 24th, that the carpenters started erecting the stage in the Open Air Dime Theatre, with plans for the first film to start shooting the following day. Only ten days before the arrival of the Lubin Company had Arizona become the 48th State; President Taft signed the statehood papers on February 14. The Lubin troupe in Douglas consisted of Mr. Melville’s assistant Webster Cullison, with W. J. Wells acting as superintendent of the crew and Harry A. Allrich along as interpreter. Other non-actors with the west traveling Lubin group, included, P. F. McCafferty as cinematographer, O. O. Jascoby, the carpenter, the property man, Dewey Crisp; a Monsieur Latour was the scenic artist and C. L. Burgess his assistant, Arthur “Buck” Taylor took the duties as hostler for the mounts needed for filming. In front of the camera, the leading-man for this Lubin troupe was Bert L. King; Romaine Fielding was cast as the heavy; Richard Wangermann, a character actor, Eml Berger for juvenile characters, Harry Ellsky in the light comedic roles; Edna Payne and Belle Bennett feminine leads and ingénues; Lucie K. Villa the female heavy; Adele Lane the soubrette and ingénue as well; with Mses. Maguire and McCafferty, and Mrs. Payne in character studies. [18] Two specially equipped train cars hauled the scenery and effects, wardrobes for forty men, as cowboys, soldiers, Mexicans or Indians. Twenty-five outfits for the ladies to appear as cowgirls, Mexicans or Indians; Saddles and bridles and other horse accoutrements for fifteen horses were also included in the traveling costume shop.[19]

One of the pictures completed in Douglas was, A Romance of the Border, which was based on, Arizona, the 1899 play written by Augustus Thomas. Production for the movie took place in Douglas and Agua Prieta, the Mexican town directly across the border from Douglas.[20] The film company intended to stay at least for two-weeks and possibly as long as four to six-weeks; the latter being the closest of the time periods for the stay in the Douglas, Arizona area. It was in March in Douglas, that Romaine Fielding saved the life of a little girl; the child walked under the legs of a horse during filming, and Fielding, remaining on his stead, deftly grabbed the girl’s dress and quickly dragged her from danger.[21] In total, four movies were produced in Douglas, some locals made it into the movies; the landscapes of the Douglas-Agua Prieta area were used to great advantage, revealing the beauty of the southeast corner of Arizona to movie patrons, both nation and world-wide.[22] Captain King’s Rescue, was another of the movies produced in Douglas, Mr. Melville utilized the military camp at Douglas, showing the enlisted men of troops E and F, of the Fourth Cavalry, and he gave parts to several officers; a well-known captain was involved in a comedy bit in the flick.[23]

Fielding in Charge:

Contrary to popular modern renditions, Fielding was not made the manager of the Lubin western branch in March of 1912, for even as late as April 24, Wilbert Melville is still referenced in that position. Fielding was still regarded only as a star of the Lubin Film Company, not yet the “manager” of the group; which publicly he would first be referred to as in July of 1912;[24] according to authors Linda Kowall Woal and Michael Woal, Fielding was made director when Melville was sent to Los Angeles to open a Lubin studio there in May.[25] When exactly Melville left is uncertain, for numerous reports still place him in Tucson at the middle of May, 1912, with no publicity releases stating the contrary.[26] While Woal and Woal have Melville leaving Tucson for Los Angeles in May, Joseph P. Eckhardt has Melville heading to Philadelphia in June and then proceeding to Los Angeles;[27] Mr. Eckhardt’s statement seems more likely, since, by the middle of September it was said of Melville that he was headed southwest, with stops in Arizona on the planning table.[28]

Lubin Southwestern Studio Three:

Tucson, Arizona: March 31-July 12, 1912

The Lubin Company left for Tucson on Saturday, March 30, 1912; at that point Wilbert Melville planned for the company to remain in Tucson for several weeks, but they would see more than three months in the Old Pueblo.

One of the many films made in Tucson was, A Western Courtship, which included a hanging scene where the sheriff (Fielding?) saves the man intended for hanging, after cutting the rope by shooting through it; Mr. Fielding was in the director’s chair for this short western.[29] Filming by Lubin was still going on in Tucson in the first week of July of 1912, with three to four hundred citizens appearing as extras in “gold rush” scene for, The Sleeper (a western, with a Rip Van Winkle wrinkle), on the Morning of the 7th. The Tucsonians who took part in the making of the film were accompanied by numerous pack and draft animals and the requisite wagons of all kinds to flesh out the scenes; this kind of large-crowd scene seems appropriate for Fielding’s style and by nearly all accounts was under his direction.[30] The crowds were brought by repeated articles in the local newspapers, so much so, that little had to be spent on the scenes; the Southern Pacific Railroad furnished a train for the mass arrival of the seekers of gold; actual gold-miners (the old-fashioned type) advised on costumes and added technical assistance to further realism for the movie.[31] “Picacho de Sentinela (Sentinel Peak, AKA “A” Mountain), was used as a backdrop for the gold-strike, and hosted a tent-city; the older part of Tucson (South Meyer) was the stand-in for the old west.[32]

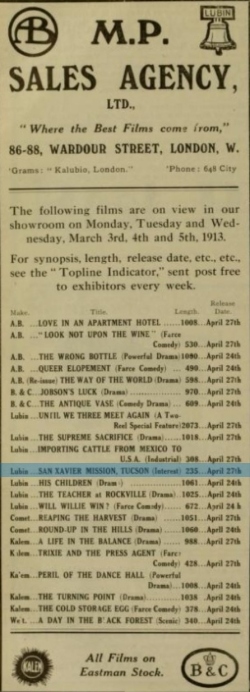

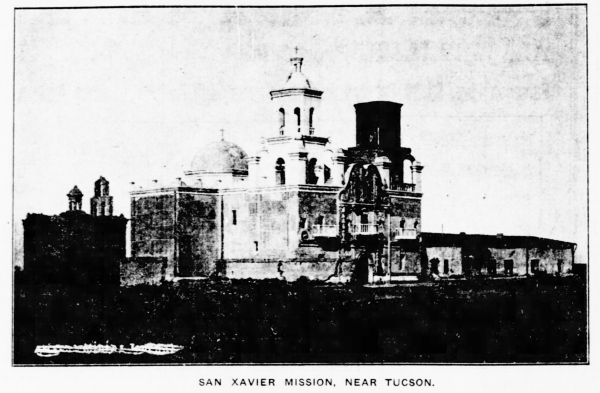

Not everything filmed by the Lubin cameras was fiction, while in Tucson, the crew made an educational movie entitled: San Xavier Mission, Tucson, Arizona, and released the documentary on January 11, 1913;[33] San Xavier is about ten-miles south of downtown Tucson. At only 235-feet, San Xavier Mission, played on the same reel as, the Lubin Eastern produced, The Artist’s Romance.[34]

San Xavier Mission about six months prior to Fielding filming there. Arizona Republican, Phoenix, Arizona, November 6, 1911

Terminating Tucson:

It was in May that Lubin was considering building a permanent studio in Arizona, the choice of location had not been determined, leaving the Tucson Chamber of Commerce in a state of courting,[35] along with Phoenix and Prescott. Phoenix was in the hunt for the Lubin Company, making a “strong bid” for this moving picture troupe; this proposed Lubin Arizona Studio was of course looked upon as a largess for the winning locale. Melville was interested in obtaining permission to use an ostrich-farm in Phoenix for one of the Lubin movies; hopes were high in the Valley of the Sun, when the manager of the Lubin Company asked about hotel rates in city.[36] Manager Melville planned a trip to Prescott with his wife, for May 15, for the purpose of seeing the local features of Prescott; Mr. Melville had had the opportunity to see over fifty photographs of Prescott and Yavapai County, and was promised by the Prescott Chamber of Commerce that Indians and other features needed for their filming would be available. This correspondence had been ongoing with the Secretary of the Chamber of Commerce, Malcolm Frazier; possibly starting as early as while the Lubin Company was still in Douglas or soon after arriving in Tucson.[37] On July 12, Lubin vacated the environs of Tucson for Prescott, resting overnight in Phoenix and continuing on toward their new home (at least what would be for a while) in Prescott.[38]

Lubin Southwestern Studio Four:

Prescott, Arizona: July 13-November 12, 1912

In particular, Fielding and the Lubin Company now under his command, had set their collective eye on Fort Whipple. Fielding’s plans were to utilize the barracks, and the surrounding hills and dales for a series of westerns; Fort Whipple was to the northeast of Prescott,[39] and was in its last year of use and would be closed in 1913.

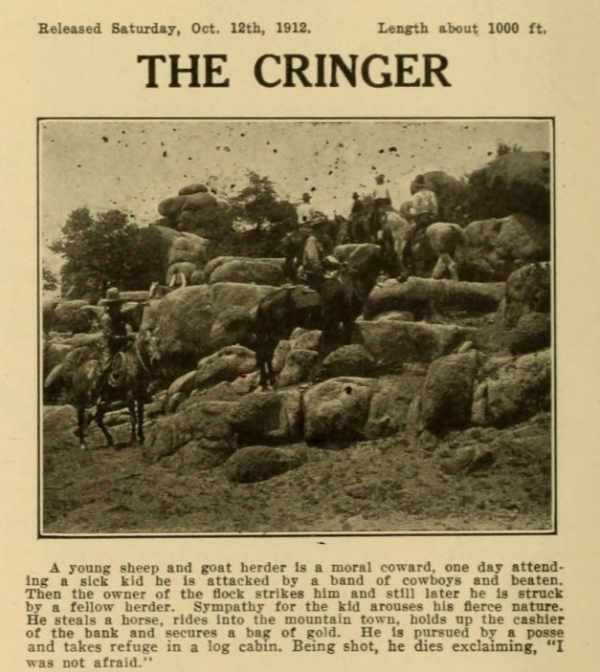

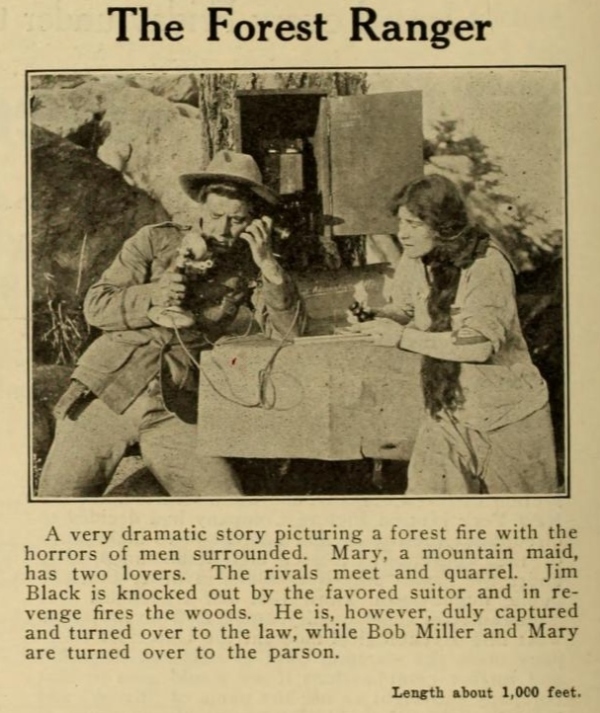

The first movie made in Prescott by Fielding was, The Cringer (a cowardly, mistreated sheep-herder, turns bank-robber and arsonist); Fielding was given permission to film at the Granite Dells, he did so with local horsemen, for certain scenes for this unusual and dark film. This production was followed soon by, The Forest Ranger (a mountain maid, two suitors, jealousy, revenge, a forest-fire, love and the law); The Forest Ranger, saw some of its scenes shot on Spruce Mountain.[40] A further title from the Prescott-Fielding film venture was, His Western Way, the story of Bob, a man whose sweetheart moves to the big city and finds a city-fellow to love; Bob, in his grief, follows after her and wins her back, in Bob’s western way.[41]

The final Prescott-Fielding film we will examine is, The Neighbors (evidently a working title for: The Family Next Door), starring Mary Ryan. The Family Next Door, included two young people in love and their elopement protected by friends who just happen to be cowboys, the newlyweds escape on a train, and finally the bride and groom’s fathers are “coddled into forgiveness.”[42] Under the direction of Fielding, Ryan attempted to jump from a horse to the rear of a moving train, but she fell and hit the tracks, causing small injuries around her face and neck and to her arms. Ms. Ryan was not to be deterred, she left the second try at the moving train with no further hurts, as she was grabbed from the horse onto the platform of the caboose by a fellow actor.[43] This second attempt for Ryan was greeted with the cheers of some three hundred people watching at the depot, amongst whom were George P. Baldwin President of the Kelvin Sultan Copper company, A. H. Westfall the general manager of the Monon route and the vice-president of Kelvin copper concern. Mrs. Westfall, L. R. Johnson, (Mr. Westfall’s personal secretary) and F. M. Murphy (President of the S. F., P. & P. lines of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad), were also in the party that witnessed the thrilling action performed by Ms. Ryan and the balance of the Lubin Company.[44]

Pressed From Prescott:

Little fanfare preceded Fielding and Lubin leaving Prescott, the length of stay (four months) in Prescott would only be surpassed by the upcoming sojourn in Nogales, Arizona. One hint is available as to moving the film company from Prescott to Nogales, and that bit of evidence comes by a certified copy of a “records letter,” received by Fielding from Ira M. Lowry, a long-time employee of (manager, director, general manager) Siegmund Lubin’s film company (later Lowry would direct for the Betzwood Film Company); this was dated in the middle of October.[45]

Lubin Southwestern Studio Five:

Nogales, Arizona: November 13, 1912-May 20, 1913

On Wednesday, November 13, 1912, Romaine Fielding and the rest of the Lubin Western Company (a stable of nineteen performers) arrived in Nogales, Arizona, and took up residence at the Montezuma Hotel.

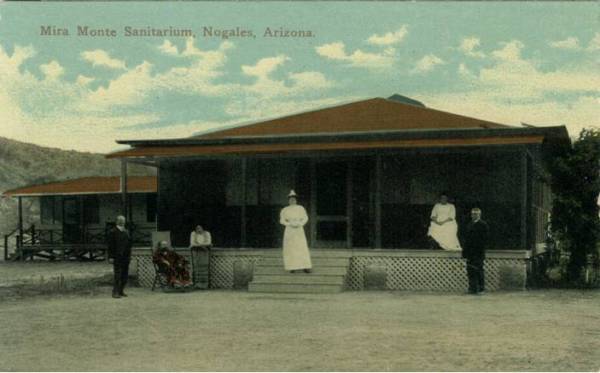

For the stay in Nogales, Fielding leased a portion of the, Mira Monte Sanitarium, and used the facility as the Lubin studio; Mira Monte was under the direction of Dr. A. L. Gustetter who along with Dr. H. W. Purdy were the physicians in control of the medical treatments at the health-resort. The sanitarium was located in the northern part of Nogales, with a view of the Santa Rita Mountains, therefore the name “Mountain View.” Mira Monte was situated in an area that was considered quiet and shielded from the winds and dust.[46]

Courtesy of: Arizona, Pre 1930, White Border Post Card Collection Section 7 — N to Phoenix 2781, by Al Ring

On Wednesday, December 4th, 1912, the Lubin cameras took a good many shots of cattle being driven down an arroyo, then into stock pens at the railway yards, and the dipping and loading process of the bovine onto the rail-cars; this footage was taken as the Alamo Cattle Company crossed 2100 head of cattle over the Mexico line.[47] Christmas day of 1912 saw a special dinner with a gift presented to Fielding by the entirety of the Lubin Western Company; the holiday repast, was held at Lulley’s Buffet, in Nogales, owned and operated by Louis Lulley.[48]

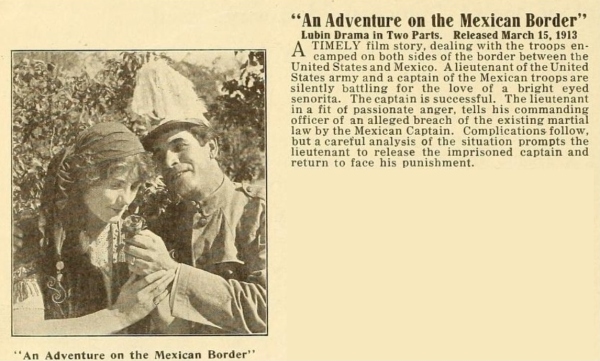

An Adventure on the Mexican Border, was a product of the Lubin Company while in Nogales; a plotline with international consequences. A Senorita gains the attention of an American Lieutenant and a Captain of the Mexican Army; the Mexican Captain wins the heart of the young lady, and the American Lieutenant, in jealousy and spite, lies to his commanding officer, nearly causing international complications. The Mexican Captain is jailed because of this false information, but finally, the conscience of the Lieutenant overcomes his feelings and, gaining the freedom of the Captain, returns him to his Senorita in Mexico; the American returns across the border, awaiting his military discipline.[49]

With the help of three troops of U. S. Cavalry, A Girl Spy in Mexico was finished at Nogales, filled with war-action, and the subterfuge of the title-character. The young senorita, Armaje, confronts the dangers of being a spy, for the purpose of being near the Lieutenant she loves; two arrests, two escapes and a march to death round out the story.[50] Also the railroad themed picture, The Weaker Mind, was produced in the border-town; really not so much a railroad film, but a morality-romance tale, with its main characters involved with the local railroad.[51]

Copper and Brotherly Love:

It was in April of 1913, that Fielding was called back to Philadelphia for business, leaving near the midpoint of April and returning in the middle of May; during the first days of his trip Romaine Fielding made a tour of the facilities of the Chino Copper Mine, in Santa Rita, New Mexico on Saturday, April 19, 1913. The purpose of this visit was to scout the area for possible locations for future films and to seek out suitable lodging; evidently, appropriate rooms for Fielding and Lubin were not easily found and Fielding was concerned that a move to Silver City would not take place. Not to be dissuaded from the schedule of his eastward journey, Romaine Fielding continued on, leaving the manager of the Chino Mine, in charge of the search for accommodations for the Lubin Western Branch; about ten-days later, billet was found for the group.[52]

Director Fielding made a stopover in El Paso and took the Shrine degree on Saturday, April 26, at the local Masonic lodge; the next stop for Fielding was Philadelphia.[53] This trip east and the west return precipitated the Lubin Western Company leaving Nogales, for Silver City, New Mexico. Although Fielding gave the impression that the company of movie-makers would stay for the foreseeable future, yet, within a week after his return, Fielding and company packed up and moved on to Silver City and would spend much time filming in Santa Rita, NM, in the vicinity of the Chino Copper Mine and the processing mill in Hurley.[54]

One could speculate why the Lubin Moving Picture Company opened its western branch studio in Silver City, New Mexico, besides the obvious topographical reasons and distance from Nogales; and the answer to that speculation was blood, family, that is. Robert Blandin, brother of Romaine Fielding, was one of the Chino Copper Company engineers and manager of the copper concern, in Santa Rita.[55] The two had reunited after fifteen or sixteen years separated; the official story ran that Robert saw the film, The Blacksmith, and recognized, Romaine Fielding as his brother. He then promptly sent a letter and the brothers met in Douglas, Arizona, on Thursday, March 21, 1912. Robert had been presumed dead by Fielding for the last fifteen years, having received word that he had been buried alive under a landslide in southern Sinoala, Mexico about 1897.[56] Robert had left New York, circa 1896 with a group of twenty civil engineers to locate and survey a new railway line in Mexico; during that first year, Robert made regular reports to family about the successful work he was involved with. Then the message from the company which Robert worked for, arrived explaining that a landslide caused by an earthquake had killed Robert along with the rest of his crew. Subsequent to their reunion, the brothers stayed in close communication over the course of next year and Romaine grew interested in his brother’s descriptions of the area around Silver City, New Mexico, but the locality played a dual role, first as a Lubin Studio location and providing an opportunity for a more extensive visit for the siblings.[57] The Lubin Western Company in the person of Romaine Fielding, gained access to the Chino Mine by agreeing to film an industrial movie for the copper company.[58]

Lubin Southwestern Studio Six:

Silver City, New Mexico: May 21-August 17, 1913

The written record regarding the Lubin Company in Silver City, offers a full picture of what Fielding and Lubin were doing, particularly with westerns. A Sunday in June, proved a thrilling day for the citizens and neighbors of Silver City when Romaine Fielding blew up a narrow-gauge railroad-bridge and two large water-tanks; the fuse failed on the dynamite and Mr. Fielding took aim with a 30-30 rifle and with one-shot set off the explosion.[59] Reportedly, the water-tanks shot up 200-feet in the air, showering the pretend-rioters and the 2000 spectators with splinters and rocks; thankfully, no one was injured. The Lubin Company crew filmed a riot scene involving no less than 200 men; following that multiple display from Sunday, on Monday (September 1, 1913), an oil house at the smelter (located below Silver City) was blown up, to become a part of the same scene as those enactments caught on celluloid on Sunday.[60]

The requisite automobile wrecking was filmed, but the unusual rescuing of a young lady in distress by utilizing a steam-shovel at the Chino Copper Mine in Santa Rita, was a stroke of genius by Fielding.[61] The necessary hold-ups of trains were filmed, along with that, a brick house that was situated near Silver City, was blown-up by the film-crew; cowboys from neighboring ranches appeared, affording the short movies a further sense of realism.[62] On Saturday, May 31 (first day the cameras rolled in Silver City), Fielding and company, gathered on Boston Hill for some “hair-raising” stunts perpetrated by a local group of riders; further scenes were acted out at the Elephant Corral on Hudson, and in the Main Street gulch. A large window in the Abraham block of Silver City, had the fictional name of, Red Onion Saloon painted on it, and was broken for the sake of film; this occurred on Sunday, June 1, by a stuntman who had been thrown through the window. The 2nd of June thousands of people from all over Grant County gathered to watch the burning of the Cousland (there are two spellings from two sources, Cousland or Consland) House, located in the northwest of town; the pyrotechnic display was offered in the morning.[63]

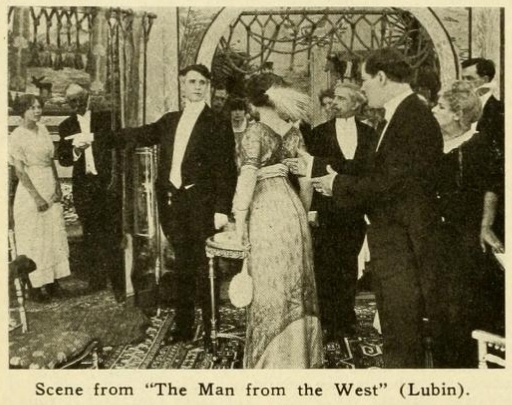

The Man From the West (AKA: The Gentleman from New Mexico), a drama contrasting the East with the West was produced in Silver City, in the summer but not released until January of 1914.[64] The Man From the West, a love story, typifying the strengths the “Man” in question, who has fallen in love with an eastern lady of high social standing and how he overcomes the societal obstacles between them.[65]

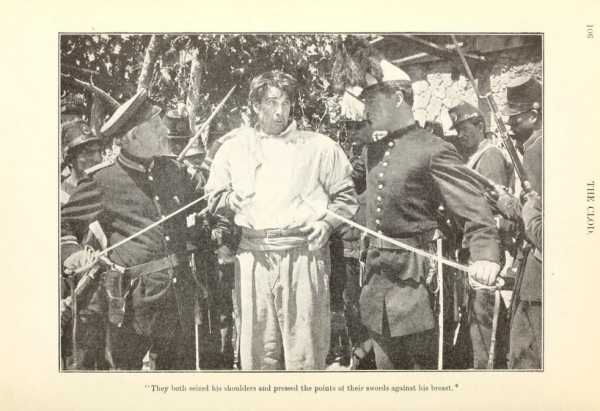

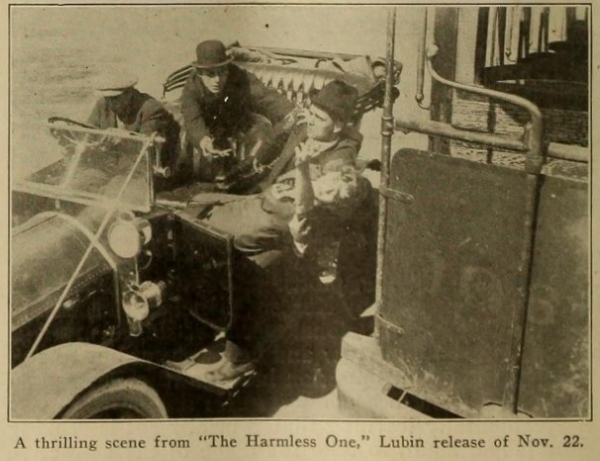

A two-reel flick, titled, The Clod, was primarily shot in Silver City, using the torn-from-the-headlines Mexican trouble for the scenario; Jess Robinson, of El Paso had a leading role in the picture, along with three other El Pasoans in support: Henry Alrich, Ms. Brockwell and Mrs. Brockwell.[66] Another film that began production in Silver City but finished later in Las Vegas was, The Harmless One; the convoluted scenario saw its opening in November of 1913. The Harmless One, is actually a sadist, inflicting pain, both physically and emotionally. As a child, The Harmless One, derives pleasure from pulling the ears of a baby, enjoying the cries of the infant; stopping, only after being forced by an adult-passer-by. His venal escapades continue with small actions, such as pulling a cat’s tail, with the story progressing with numerous deeds of a “perverted nature.” The crux of the tale provides a fiendish culmination, with the adult-Harmless One (Fielding in the role) setting his sights on a young woman; a runaway trolley and a speeding auto, play major parts the finale.[67]

Four for Seven:

The company of Lubin actors, and behind the scenes professionals had grown from twenty-five in Prescott, to over fifty in the traveling movie troupe in Silver City;[68] by the early part of July, 1913, Romaine Fielding was looking to move the location of the Lubin Moving Picture Company western-branch studio from Silver City, New Mexico to another clime. Two Land of Enchantment cities, and two towns that had previously acted as bases for Lubin, offered their services to Fielding, each community posing a strong case for the relocation.

Let me include a little back-story on each city that vied for the Lubin Western Studio; beginning with the two that had already hosted Fielding and the Lubin group. Tucson, even though mentioned, according to at least one report,[69] as Fielding’s favorite in the Southwest, was never a contender. No further invitations or special privileges were granted from the Old Pueblo, to induce Fielding to come back; or at the least nothing was made public by the Chamber of Commerce in Tucson. This reporter has found no indication that Fielding made a return trip to investigate or film in Tucson, during his stay in Silver City.

The second municipality on this list of nominees, was actually the first city visited by Fielding on this relocation-tour: El Paso. El Paso, as Tucson, does not in retrospect, appear to have made a strong argument for the transfer of the Lubin movie company. No efforts are recorded that the these two cities courted, Fielding; Fielding, it is clear a hundred-years hence, enjoyed the courting process and this lack of wooing by Tucson and El Paso may have swayed his opinion to the negative for the Old Pueblo and the Sun City.

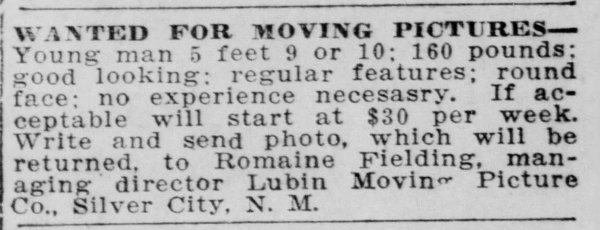

At the middle of June of 1913, former El Pasoan and actor, Jess Robinson, was in the Sun City making arrangements for Fielding and the rest of the Lubin Company, for an upcoming location shoot in El Paso.[70] Then on June 27, 1913, Romaine Fielding placed two want-ads in the El Paso Herald, asking for a young man and a young lady for a part in a moving picture. The ads were repeated in the Saturday, June 28, edition of the same paper. These advertisements occasioned Fielding traveling from Silver City, New Mexico to El Paso, Texas on Monday, June 30, 1913, to put the finishing touches on, A Gentleman from New Mexico. For Monday, June 30, and Tuesday, July 1, Fielding ran an ad in the El Paso Herald, offering an open call for anyone, interested the previous, Wanted for Moving Pictures, ads, to be at the Sheldon Hotel between 8 and 9 PM, that same evening.

Fielding and crew were in El Paso, to complete the story-line of the aforementioned, A Gentleman from New Mexico, (The Man From the West), which ends with the title character leaving New Mexico and going to El Paso.[71] The celluloid action took in several views on Montana Street and Houston Square, with well-known sites such as The Herald Building, Pioneer Plaza, The Mills Building, The Sheldon Hotel, Union Station and W. W. Turney’s residence included in the scenes. The film group was set to return to Silver City later in the week.[72]

It was in the days leading up to the Fourth-of-July celebration, that El Paso believed they had been chosen as the next (albeit, it would have been the second time around for El Paso: January-February of 1912) western-branch studio for Lubin and Fielding.[73] Now either, El Paso and the next city to be reflected on, Albuquerque, misunderstood the attentions of Mr. Fielding or he was undecided on where to locate next, and let his compliments convey too much assurance to the local dignitaries. Or, as he had done in Nogales, Arizona, committed to one and quickly changed his mind.

The next two towns considered by Fielding, were New Mexico communities, and both of these with wide open arms of hospitality, made available to Fielding, the key to the city, so to speak. The first of the New Mexican townships and third stop for the Lubin-Fielding relocation-express was Albuquerque; those in the know in the Burque, felt assured that Fielding had already made the decision, and was to make Albuquerque home for Lubin. On July 24, Fielding toured the city, accompanied by Joseph Barnett and H. E. Sherman of the Barnett Amusement Company, while also visiting with the Mayor of Albuquerque, D. K. B. Sellers.[74] The gracious and cordial meeting of Fielding and the Albuquerque representatives were, inferred to be perfunctory conferences, serving to initiate the relations between the Lubin Moving Picture Company’s western-branch studio, Fielding and Albuquerque, rather than wooing the company to the environs of the Duke City. The article (found in the Albuquerque Evening Herald) related that Fielding had received instructions to go to Albuquerque after finishing up the work in Silver City; what a disappointment when the Lubin-Fielding company decided for another destination.[75] I believe that those involved in the negotiations with Fielding in Albuquerque, on July 24, overlooked the tale-tale sign that Fielding left earlier than expected. The manager of Lubin’s western-branch studio and the person with the final decision, had indicated that he intended to spend several busy days in Albuquerque, but Fielding left, less than forty-eight-hours after he had arrived.

The final of the four cities, and the second in New Mexico for the possible location of the new Lubin studio, was one-hundred-twenty-five-miles northeast of Albuquerque and a quick jaunt for Fielding: Las Vegas, New Mexico. Obviously, three four-is-a-charm; the Commercial Club (the local chamber of commerce[76]) had invited Fielding, in early July, to move the Lubin studio from Silver City, New Mexico. He met on Saturday, July 26, in the afternoon with Las Vegas banker Hallett Raynolds, the Secretary of the Commercial Club, W. H. Stark; the group of enthusiastic welcomers also included representatives of the Duncan and Browne Moving Picture Theater, George Fleming and H. P. Browne.[77]

The party of Las Vegas VIP’s escorted Fielding by automobile to the sights most advantageous for an afternoon drive. They spent the night at El Porvenir, the accommodations there I would assume were provided either at the El Porvenir Dude Ranch or the Y. M. C. A. campground (which had just opened earlier that summer). On Sunday they took the short hike to Hermit’s Peak. Here the group of Las Vegans may have sealed the deal with their pre-planned exploit. Communication was established between fifteen people in Las Vegas, from Hermit’s Peak via heliograph (telegraph flashes from a mirror). Fielding was delighted with the experiment and said he would use a similar stunt in an upcoming film, which he was currently writing the scenario for.[78] Although time was limited for Fielding, and not in a position to take in very many scenic sights, still, he was able to see enough to convince him of the beauty of the area and commented that he was surprised that Las Vegas was not better advertised to the country. While in town Fielding did visit the Duncan and Browne Theater, and was satisfied with the screens and machines in use and felt them excellent and capable of producing high grade quality motion pictures.[79]

W. Hugh Stark played the biggest part in bringing Romaine Fielding and the western-branch studio of the Lubin Company to Las Vegas, seeing it was his initiative that started the courtship with Fielding.[80] Fielding stated that “he would never have thought of Las Vegas as a place for the production of moving pictures.” So, without Stark, Fielding would most likely have followed the behest of the Lubin home office and ended up in Albuquerque, but Stark had tendered a cohesive and attractive presentation and thereby won the Lubin Western Branch Film Company sweepstakes; albeit a prize that would last for only a short ninety-days.[81] Romaine Fielding having accepted the invitation proffered by Las Vegas, targeted a move by date of around August 18th.[82]

Lubin Southwestern Studio Seven:

Las Vegas, New Mexico: August 18-November 23, 1913

The Lubin moving picture company western studio, headed by Fielding, took up residence at 920 Gallinas Street. Fielding had the house prepared as a studio for the indoor scenes (obviously, the make-shift studio did not work as he planned, for some interiors were shot in Galveston[83]) and permanent living quarters were obtained by Fielding when he leased the Plaza Hotel, in late September, providing rooms for the eleven (his staff while in Silver City was twenty-five; eleven may be a case of misreporting[84]) cameramen, actors and actresses that made up his company.[85]

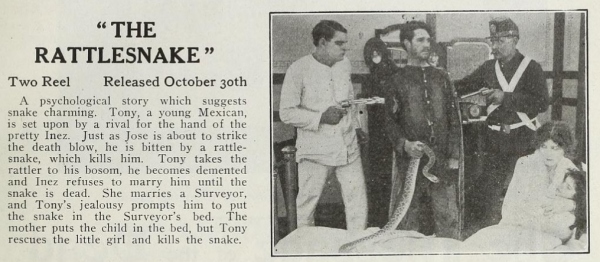

Fielding and the Lubin crew were quite busy in Las Vegas, filming at an accelerated rate; making the most of what turned out to be the final weeks of the Lubin Film Manufacturing Company southwestern branch experience. The Rattlesnake, a well-remembered production by the citizens of Las Vegas, had a scenario, twisted enough to match the movements of a rattler, and featured a rattlesnake captured south of Juarez, Mexico, and transported to Las Vegas. El Pasoan, Jesse Robinson, who had started as an actor for Fielding in Silver City, was in, The Rattlesnake.[86]

The Harmless One, was scheduled (weather permitting) to wrap up filming on September 4, 1913, several houses and business were used for exterior shots, including the town’s electric trolley car; as aforesaid, The Harmless One had begun production while the film company was still in Silver City.[87] His Blind Power (AKA: The Blind Power), reached a pinnacle of scenes shot in one day, on Monday, September 29, with thirty finished milieus; the film was on pace to wrap by the end of the first week of October.[88] In addition, The Evil Eye (a plotline based upon rural ignorance and superstition[89]), and, The Higher Law (starring Arthur Johnson as self-sacrificing District Attorney in a court-drama[90]) were made while Fielding acted as manager and director of the Lubin Company in Las Vegas; and not forgetting Fielding’s last project in this New Mexico Township: The Golden God.[91]

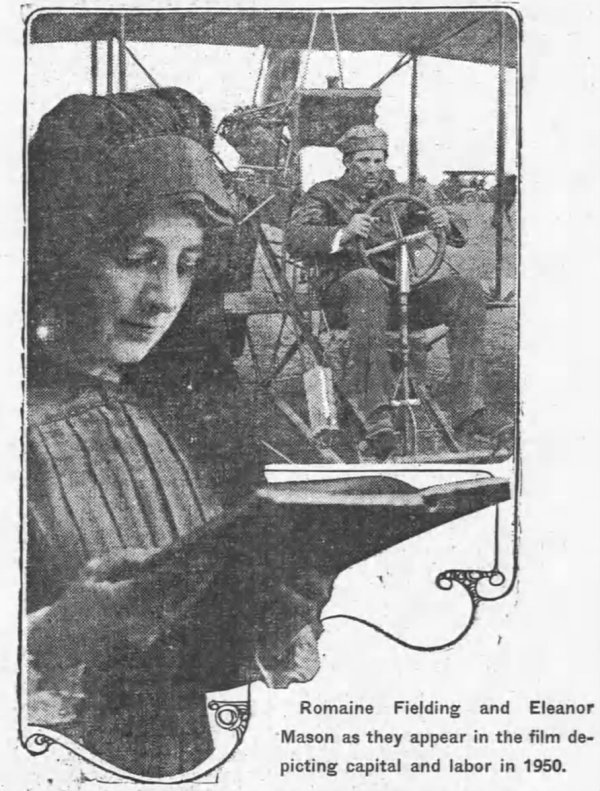

Some writers have mistakenly reported that, The Golden God, began filming in the summer of 1913, but, this does not jibe with Romaine Fielding’s own account, that in September of 1913, he was shooting, The Rattlesnake, in Las Vegas, New Mexico.[92] With plans for large crowd scenes, the original idea of the five-thousand-extras for, The Golden God, was set for El Paso, Texas, near Fort Bliss; as well there were plans for an additional two or three thousand for the big battle scene.[93] This bit of information was seen in the El Paso Herald, on November 10, 1913; obviously then, The Golden God, had not commenced production as so many have detailed. Eleanor Mason, who co-starred with Fielding in, The Golden God, was also Fielding’s tireless personal secretary.[94] For a more thorough look at, The Golden God, please see my article posted on Classic Film Aficionados.

Leaving Las Vegas:

On November 7, Romaine Fielding addressed the newly formed University Club of Las Vegas on the subject of, The Moving Picture as an Educational Force.[95] Just two-weeks and two-days later, on November 23, 1913, after the last of the exterior scenes of, The Golden God, were in the can, Fielding left Las Vegas with plans to spend the winter at the Lubin Galveston, Texas, studio.[96]

Portions of this article appeared in: The Golden God, a Glaringly Giant Gap in the Glowing History of the Glamorous Art of Cinema; Not Seen and Little Known. Those paragraphs and snippets included from the previous commentary, may be found in this document commencing with, Copper and Brotherly Love, and followed by the Silver City, Four for Seven and Las Vegas sections.

By C. S. Williams

Recommended Reading:

Location Filming in Arizona: The Screen Legacy of the Grand Canyon State, By Lili DeBarbier, published by, The History Press, 2014, pages 24-25, 98-100

Early Movie Making comes to Prescott, 1912, By Mona Lange McCroskey, published in, Territorial Times, Volume IV Number 2, Spring 2011, pages 8-15

The King of the Movies: Film Pioneer Siegmund Lubin, by Joseph P. Eckardt, published by, Associated University Presses, 1997

Early Film Making In New Mexico: Romaine Fielding And The Lubin Company, by Robert Anderson, published in the New Mexico Historical Review, Vol 51, No 2: April, 1976

Romaine Fielding’s Real Westerns, By Linda Kowall Woal and Michael Woal, published in, Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 47, No. 1/3, The Western, Spring-Fall 1995, pages 7-25

Film & Photography on the Front Range (Romaine Fielding & the Lubin Manufacturing Company, by Kenneth Paul Fletcher), edited by Tim Blevins, published by Pikes Peak Library District, 2012, pages 141-167

Las Vegas (Images of America), by Mitch Barker, published by Arcadia Publishing, 2013, page 51

Gateway to Glorieta: A History of Las Vegas, New Mexico (a part of the Southwest Heritage Series), by Lynn Irwin Perrigo, Ph.D., published by, Sunstone Press, 2010, pages 48-49, 195

In Search of Western Movie Sites, by Carlo Gaberscek and Kenny Stier, published by, A CP Entertainment Books, 2014, pages 1, 20, 49-50

[1] Dramatic Mirror, January 24, 1912

[2] Dramatic Mirror, January 24, 1912

Motion Picture Story Magazine, February; March; August, 1912

[3] Motion Picture Story Magazine, April, 1912

[4] Motion Picture Story Magazine, May, 1912

[5] Dramatic Mirror (New York, New York) April 17, 1912

Motion Picture Story Magazine, June, 1912

[6] The King of the Movies: Film Pioneer Siegmund Lubin, by Joseph P. Eckhardt, published by Associated University Presses, 1997, page 127

[7] Dramatic Mirror (New York, New York) January 24; 31, 1912

[8] Bisbee Daily Review (Bisbee, Arizona) February 25, 1912

[9] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) February 15, 1912

[10] Mount Carmel Item (Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania) March 26, 1912

Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) April 2, 1912

Fort Scott Daily Monitor (Fort Scott, Kansas) April 18, 1912

[11] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) March 25, 1912

Fort Scott Daily Monitor (Fort Scott, Kansas) April 13, 1912

Concord Daily Tribune (Concord, North Carolina) May 29, 1912

[12] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) February 7, 1912

[13] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) February 6, 1912

[14] Allentown democrat (Allentown, Pennsylvania) February 3, 1912

[15] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) February 5, 1912

[16] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) April 8, 1912

[17] Bisbee Daily Review (Bisbee, Arizona) February 25, 1912

[18] Bisbee Daily Review (Bisbee, Arizona) February 25, 1912

[19] Bisbee Daily Review (Bisbee, Arizona) February 25, 1912

[20] Bisbee Daily Review (Bisbee, Arizona) July 18, 1912

[21] Dramatic Mirror (New York, New York) March 20, 1912

[22] Tombstone Weekly Epitaph (Tombstone, Arizona) March 31, 1912

[23] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) May 8, 1912

[24] Bisbee Daily Review (Bisbee, Arizona) February 25; March 17, 1912

Tombstone Weekly Epitaph (Tombstone, Arizona) March 31, 1912

Weekly Journal Miner (Prescott, Arizona) July 17, 1912

Dramatic Mirror (New York, New York) July 17, 1912

[25] Romaine Fielding’s Real Westerns, By Linda Kowall Woal and Michael Woal, published in, Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 47, No. 1/3, The Western, Spring-Fall 1995, pages 7-25

[26] New York Clipper (New York, New York) May 18, 1912

[27] Romaine Fielding’s Real Westerns, By Linda Kowall Woal and Michael Woal, published in, Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 47, No. 1/3, The Western, Spring-Fall 1995, pages 7-25

The King of the Movies: Film Pioneer Siegmund Lubin, by Joseph P. Eckhardt, published by Associated University Presses, 1997, page 128

[28] Motography, September 14, 1912

[29] Auburn Citizen (Auburn, New York) August 8, 1912

[30] Tombstone Epitaph (Tombstone, Arizona) July 7, 1912

Romaine Fielding’s Real Westerns, By Linda Kowall Woal and Michael Woal, published in, Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 47, No. 1/3, The Western, Spring-Fall 1995, pages 7-25

In Search of Western Movie Sites, by Carlo Gaberscek and Kenny Stier, published by, A CP Entertainment Books, 2014, page 1, 50

Location Filming in Arizona: The Screen Legacy of the Grand Canyon State, By Lili DeBarbier, published by, The History Press, 2014, page 25

[31] Romaine Fielding’s Real Westerns, By Linda Kowall Woal and Michael Woal, published in, Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 47, No. 1/3, The Western, Spring-Fall 1995, pages 7-25

In Search of Western Movie Sites, by Carlo Gaberscek and Kenny Stier, published by, A CP Entertainment Books, 2014, page 1, 50

[32] In Search of Western Movie Sites, by Carlo Gaberscek and Kenny Stier, published by, A CP Entertainment Books, 2014, page 1, 50

Location Filming in Arizona: The Screen Legacy of the Grand Canyon State, By Lili DeBarbier, published by, The History Press, 2014, page 25

[33] Motography, January 18, 1913

[34] The Cinema, March 26, 1913

Fairbanks Daily Times (Fairbanks, Alaska) July 30, 1914

[35] Motography, May, 1912

[36] Arizona Republican (Phoenix, Arizona) April 11, 1912

Weekly Journal Miner (Prescott, Arizona) April 24, 1912

[37] Weekly Journal Miner (Prescott, Arizona) April 24, 1912

Early Movie Making comes to Prescott, 1912, by Mona Lange McCroskey, published in, Territorial Times, Volume IV Number 2, Spring 2011, pages 8-15

[38] Arizona Republican (Phoenix, Arizona) July 13, 1912

[39] Arizona Republican (Phoenix, Arizona) July 13, 1912

[40] Moving Picture World, October 5; 26, 1912

Early Movie Making comes to Prescott, 1912, by Mona Lange McCroskey, published in, Territorial Times, Volume IV Number 2, Spring 2011, pages 8-15

[41] Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, Pennsylvania) March 18, 1913

Border Vidette (Nogales, Arizona) March 22, 1913

[42] Mount Carmel Item (Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania) November 21, 1912

Moving Picture World, October 26; November 2, 1912

Early Movie Making comes to Prescott, 1912, by Mona Lange McCroskey, published in, Territorial Times, Volume IV Number 2, Spring 2011, pages 8-15

[43] Arizona Republican (Phoenix, Arizona) July 24, 1912

[44] Arizona Republican (Phoenix, Arizona) July 24, 1912

[45] Variety, April 8, 1908

New York Clipper (New York, New York) May 11, 1912

Weekly Journal Miner (Prescott, Arizona) November 27, 1912

[46] Weekly Journal Miner (Prescott, Arizona) July 17, 1912

Border Vidette (Nogales, Arizona) November 16, 1912

El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) November 23, 1912

The Oasis (Arizola, Arizona) December 25; 28, 1912

Arizona: Prehistoric – Aboriginal – Pioneer – Modern, Biographical, Volume III, by James H. McClintock, Published by S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1916, pages 941-942

[47] Coconino Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona) December 6, 1912

[48] Tombstone Epitaph (Tombstone, Arizona) January 5, 1913

[49] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) March 29, 1913

[50] Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana) May 21, 1913

El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) July 26, 1913

[51] Fort Wayne Journal Gazette (Fort Wayne, Indiana) June 19, 1913

El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) July 26; September 2, 1913

[52] Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) April 24, 1913

Early Film Making In New Mexico: Romaine Fielding And The Lubin Company, by Robert Anderson, published in the New Mexico Historical Review, Vol 51, No 2: April, 1976

[53] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) April 28, 1913

Border Vidette ( Nogales, Arizona) May 17; 24, 1913

Early Film Making In New Mexico: Romaine Fielding And The Lubin Company, by Robert Anderson, published in the New Mexico Historical Review, Vol 51, No 2: April, 1976

[54] Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) April 24, 1913

[55] Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) April 24, 1913

Border Vidette (Nogales, Arizona) July 19, 1913

[56] Bisbee Daily Review (Bisbee, Arizona) March 17, 1912

[57] Bisbee Daily Review (Bisbee, Arizona) March 17, 1912

Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) April 24, 1913

[58] Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) April 24, 1913

[59] Moving Picture News, September 6, 1913

Early Film Making In New Mexico: Romaine Fielding And The Lubin Company, by Robert Anderson, published in the New Mexico Historical Review, Vol 51, No 2: April, 1976 (eyewitness account of Lehn Engelhart, in his interview with Phillip St. George Cooke, on February 11, 1970)

[60] Moving Picture News, September 6, 1913

Early Film Making In New Mexico: Romaine Fielding And The Lubin Company, by Robert Anderson, published in the New Mexico Historical Review, Vol 51, No 2: April, 1976

[61] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) June 16, 1913

[62] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) June 6, 1913

[63] Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) June 5, 1913

Early Film Making In New Mexico: Romaine Fielding And The Lubin Company, by Robert Anderson, published in the New Mexico Historical Review, Vol 51, No 2: April, 1976

[64] Dramatic Mirror (New York, New York) January 14, 1914

[65] Houston Post (Houston, Texas) January 26, 1914

[66] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) November 8; 12, 1913

[67] Las Vegas Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) September 3, 1913

[68] Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) July 7, 1913

[69] Border Vidette (Nogales, Arizona) July 19, 1913

[70] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) June 16, 1913

[71] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) June 30, 1913

[72] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) June 30, 1913

[73] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) June 30, 1913

[74] Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) July 24, 1913

[75] Evening Herald (Albuquerque, New Mexico) July 7, 1913

[76] Las Vegas Daily Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) July 28, 1930

[77] Las Vegas Daily Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) July 28, 1930

[78] Las Vegas Daily Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) July 28, 1930

[79] Las Vegas Daily Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) July 28, 1930

[80] Santa Fe Trail Magazine, Volume One, Number Three, September 1913

[81] Las Vegas Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) July 28, 1913

[82] Las Vegas Daily Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) July 28, 1930

[83] Las Vegas Daily Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) July 21, 1930

[84] Las Vegas Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) July 28, 1913

[85] Las Vegas Daily Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) August 13, 1976

[86] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) December 19, 1913

[87] Las Vegas Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) September 3, 1913

[88] Las Vegas Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) September 30, 1913

[89] Motography, November 1, 1913

[90] Winnipeg Tribune (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) October 28, 1913

Lima News (Lima, Ohio) October 31, 1913

[91] Las Vegas Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) March 27, 1974

[92] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) September 21, 1913

[93] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) November 10, 1913

[94] The Day Book (Chicago, Illinois) March 3, 1914

[95] Las Vegas Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) October 28, 1913

[96] El Paso Herald (El Paso, Texas) January 8, 1914

Las Vegas Daily Optic (Las Vegas, New Mexico) August 13, 1976