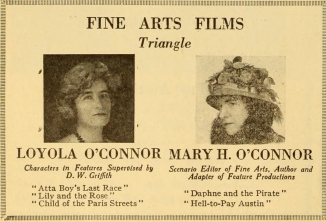

Mary Hamilton O’Connor was the daughter of Thomas J. O’Connor and Bridget Nash O’Connor; Mrs. O’Connor was a writer as well, a dramatic critic for local Portland, Oregon newspapers, and was a special correspondent for the Oregonian.[1] Her sister was actress Loyola O’Connor-Johnson (forty-eight film appearances-all silent) and the aunt of assistant-director Richard Johnson (Brewster’s Millions, 1921, starring Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle… all of Johnson’s work was in non-talkies).

The O’Connor family moved to Portland, Oregon, from Minnesota, when Mary was not much for than an infant, in the early 1870’s. She lived in the City of Roses until 1895 (22-23 years of age), when she moved to San Francisco. The months that O’Connor resided in the City by the Bay, she wrote for the San Francisco Examiner, offering special articles and juvenile stories. Not too long after her move to northern California, O’Connor decided to go where the literary action was, to New York City. Whilst in New York, O’Connor contributed to various publications, and did some reporting for one of the New York City metropolitan newspapers.[2]

Mary Hamilton O’Connor’s literary career began in earnest in 1898, with an article in, Trained Motherhood, for their February edition;[3] then a piece for the, Decorator and Furnisher, journal in the same month.[4] She followed with an articles in Ev’ry Month Magazine, [5] and began what was to be a three-year relationship with Munsey publications, writing for The Puritan: A Magazine for Gentlewomen and for The Junior Munsey;[6] numerous articles, were seen in, The Puritan over the next three years. Articles too many to make mention of here were penned by O’Connor, with additional works published in, Good Housekeeping, March 1906;[7] Youth’s Companion, The American Boy and St Nicholas[8] in 1910. Furthermore, in 1910, O’Connor had a story published in, New Idea Woman’s Magazine.[9] Over the course of four years (1910-1913), Country Life in America printed two O’Connor articles.[10]

Although born in Minnesota, O’Connor, having moved to the great-north-west as a young child, had her writing influenced greatly by the area. Not only was, The Girl Homesteader, set in the north-west but her young-adult novel, The Vanishing Swede (1905), had its heart and action in the forests of Oregon, with a subplot of filing a claim; her book was well received,[11] and clearly O’Connor had a knack for communicating her passion and fascination for the great-outdoors. Her younger sister Alice designed the cover for, The Vanishing Swede; Alice had just graduated from the Cooper Art Institute of New York.[12]

Ms. Mary O’Connor was living part time in Stamford, Connecticut in 1905,[13] I assume because of the proximity to New York and the publishers so numerous so easily contacted; with the exception of a few articles that she wrote while she was a scenarist, this effectively was the end of her literary career.

Mary Hamilton O’Connor began her Hollywood writing stage by the connections of her older sister Loyola O’Connor-Johnson. Of this there seems to be little doubt.

Loyola was a successful stock-company stage actress in Portland, and got her break in movies via a letter of introduction from J. Stuart Blackton, to Rollin Sturgeon, who was the production manager at the Vitagraph west-coast studio. Loyola went to work at Vitagraph in 1912 and was immediately placed in that company’s stock of players.[14] In 1914, Mary O’Connor would work directly under Sturgeon; this seems too much of a coincidence, and appears more her sister’s influence.[15]

When first hired by the Vitagraph Company of America, in March of 1913,[16] O’Connor was facing an incredible burden as she began at her new position as a scenarist, her father, Thomas J. O’Connor was ill, and passed away on April 25, 1913[17] not long after she had started the writing assignment. M. H. O’Connor wrote at a torrid pace, penning nineteen scenarios in just six weeks in the spring of 1913; collecting and cashing checks for five scripts in one week in 1914.[18] When not penning scenarios she stayed busy by occasionally reporting for the local newspaper in Santa Cruz, California[19] and writing for Hollywood trades, such as Motion Picture Magazine and her piece on the young actress Myrtle Gonzalez, in 1914, for the, Chats With the Players, section of the magazine.[20]

To say that Mary Hamilton O’Connor was industrious might be an understatement. She bided time between her writing gigs as a, special-feature-reader for Rollin S. Sturgeon (manager of the western Vitagraph studio, a director and writer), and she acted as the west-coast representative for various literary agents and publishing firms, who controlled the motion picture rights to the works of famous authors and playwrights.[21] Working with Frank Woods, in 1915-1917, one of O’Connor’s responsibilities was to set in on the subtitle conferences.[22] In 1918, O’Connor was the assistant to Frank Woods, production manager of Lasky;[23] while a sometimes film-editor and researcher.[24]

By October of 1914, Mary and her sister Loyola sold their ranch in Santa Cruz and bought a home in Los Angeles.[25] This was not the only Hollywood collaboration between the sisters, Loyola, appeared in Tangled Threads, written by her sister Mary, of course, they also both worked on Intolerance, 1916, each with no credit. As well these two O’Connor women, worked together on, Nina, the Flower Girl, 1917, and their last film association was in Cheerful Givers, which was made in 1917.

In 1914 with, Romance of Sunshine Alley, O’Connor started her relationship with Mutual Film, writing for the different production companies in the Mutual stable; O’Connor’s final Mutual project was, Infatuation, in 1915. From Mutual she landed with the Fine Arts Film Company and Triangle Distributing, as chief of scenario writers (the only woman to hold the position at that time)[26] and her first title with FAM-Triangle was, The Penitentes; she stayed with Fine Arts-Triangle, through, Souls Triumphant, in 1917. Mary O’Connor retained the position of chief of the scenario department, until she left the company.

Further, in 1917 O’Connor wrote, A Girl of the Timber Claims, directed by Paul Powell and starring Constance Talmadge and Allan Sears; the scenario was based on her own novel, The Girl Homesteader. Although impossible to know exactly when, The Girl Homesteader was published; we are assured that it was, by a biographical article in the Oregon Daily Journal.[27] At the least we may bracket the writing of, The Girl Homesteader, sometime between 1900 and 1912, for O’Connor had not written a piece of fiction as of 1900 and would not have the time after 1912.[28] O’Connor acted as facilitator for the Fine Arts Film Company and the city of Santa Cruz, California, where she thought the area would fill in nicely for Oregon for the, A Girl of the Timber Claims, project.[29]

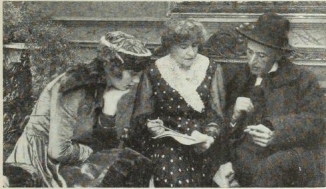

Photoplay Magazine July 1917 Constance Talmadge, Mary Hamilton O’Connor and Frank Woods; Looking over the scenario of, The Girl of the Timber Claims

Then, in 1918, O’Connor for a two-year span, worked as an assistant to Frank Woods, with no scenarios filmed; finally she saw a script produced by Famous Players-Lasky Corporation-Paramount Pictures in 1920, with, The Sins of Rosanne. She finished her Hollywood writing career and her stint with FPL-Paramount with, Dangerous Lies, in 1921, whose work was done at the Lasky British studio.[30]

O’Connor moved from writing scenarios to becoming the head of the story department at Paramount, at the west coast studio.[31] The reason for the shift for O’Connor from active scenarist to the head of a story department is summed up in an assessment by Variety, “Her judgment regarding what will or what won’t make screen material is about as infallible as that of erring human beings can be.”[32] She continued in that position until January of 1926, when Famous Players closed their story department at the West Coast Studios, O’Connor promptly resigned.[33]

Tabloid Notes and Other Reports:

It is apparent that O’Connor had her share of uncredited and or unlisted work. Her first scenario that was seen on the silver-screen was released on, March 17, 1913, St. Patrick’s Day.[34] We will probably never know for a certainty which Vitagraph movie it was, but, it may have been, The Mouse and the Lion. This is the only Vitagraph picture slated for release on March 17 of that year.[35] W. A. Tremayne is listed as the writer and Van Dyke Brooke the director and star. This portion, prior to the opening of, Thieves (her first credited work, which premiered in November of 1913), is a murky-pool-narration at best of O’Connor’s work-history; remembering that she turned-out 19 scenarios, in her first six-weeks,[36] most of those titles will never be identified. But, this first project, I highlight, After the Honeymoon, [37] is no doubt one of those nineteen scenarios she wrote, when first she arrived at Vitagraph. The film was a one-reeler, which opened the week her father, Thomas, became seriously ill.[38] It was released on April 16, 1913, and Hanson Durham is the writer of record for the comedy, which was directed by Rollin S. Sturgeon at the helm, starring Robert Thornby and Mary Charleson.

The Mutual Film production of, Jordan Is a Hard Road, 1915, based on the novel of the same name, written by Gilbert Parker is a further example of writing without attribution; we do know that at least she was given control of the first treatment of the book.[39] Indeed, the scenario may be attributable to O’Connor; this is alluded to by Frederic Lombardi, in his history-biography: Allan Dwan and the Rise and Decline of the Hollywood Studios.[40] I will go a step further and say that O’Connor did write the scenario for, Jordan is a Hard Road, by the past tense wording in a one-paragraph note in a Hollywood trade magazine in 1915.[41] Also in 1915, A Man’s Prerogative, which is credited to Frank E. Woods, but, the Motion Picture News Studio Directory, of 1916, gives that honor to O’Connor.[42] 1915 was also the year that, The Lamb, premiered, starring Douglas Fairbanks, written by Granville Warwick. Actually, Warwick was a pseudonym that Griffith used when a story came from a collaborative effort from his scenario department; Griffith, Frank Woods and Mary O’Connor were the parties responsible for it.[43] One film that is completely missed in Ms. O’Connor’s résumé is, The Birth of a Nation, on which she did most of the titling for that epic picture.[44]

O’Connor is uncredited and unlisted for her writing for a film based upon Henrik Ibsen’s play, Pillars of Society (original title: Samfundets støtter), 1916; Raoul Walsh directed, Loyola O’Connor had a small role and the only writing credit given was for Ibsen himself. But we do have a report from the Motion Picture News stating that O’Connor was preparing the scenario.[45] In another D. W. Griffith project, where O’Connor’s contribution has been forgotten is the 1916 adventure-drama, Daphne and the Pirate, starring Lillian Gish and directed by Chirsty Cabanne;[46] Griffith receives the sole credit for writing Daphne. And yet still one more David Wark Griffith project in which O’Connor is uncredited is, Intolerance, 1916, as with her work on, The Birth of a Nation, with Intolerance, she did most of the title work.[47]

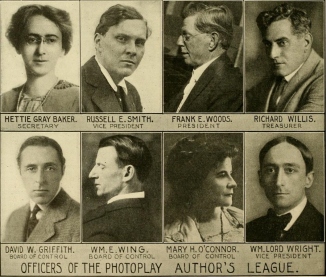

O’Connor was active in Hollywoodland, a member of the Writers’ Guild and a champion of early Hollywood.[48] She sat on the board of control of the Photoplay Authors’ League of America, along with D. W. Griffith and W. E. Wing.[49]

Also she was a council member, and eventually a member of the executive board, of The Screen Writers’ Guild.[50] Although, no longer writing for Hollywood, O’Connor continued to be active in the Los Angeles writing community, not only a member of the Los Angeles Writers Club, with other well know script-writers, Preston Sturgis (AKA: Sturges) and Frank Woods (the same Woods, that O’Connor was assistant to) and Los Angeles newspaperman, Lee Shippey, but she also sat on the board of directors;[51] while a vice-president in 1927[52] and in 1936, she was the treasurer of the same group.[53]

Mary O’Connor appeared before the cameras, albeit just in one role, in, Her Faith in the Flag, released in December of 1913. Although billed as Mary O’Connor, yet the H. soon found its way into an advertisement[54] for the short-film and the cat was out of the bag, so to speak.

By C. S. Williams

[1] Sunday Oregonian (Portland, Oregon) June 11, 1905

[2] Morning Oregonian (Portland, Oregon) March 20, 1900

Sunday Oregonian (Portland, Oregon) June 11, 1905

Moving Picture World, January 13, 1917

[3] Record-Union (Sacramento, California) February 20, 1898

[4] Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) February 25, 1898

[5] Book Notes, Monthly Literary Magazine and review of New Books, October, 1898

[6] Book Notes, Monthly Literary Magazine and review of New Books, October, 1898

The Puritan, May 1899

The Puritan, August of 1899

The Puritan, September, 1899

The Puritan, October, 1899

The Puritan, December, 1899

The Puritan, January, 1900

The Puritan, February, 1901

The Junior Munsey, September 1901

[7] Good Housekeeping, March, 1906

[8] Sunday Oregonian (Portland, Oregon) June 11, 1905

Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon) May 29, 1921

[9] Shiner Gazette (Shiner, Texas) May 19, 1910

[10] Country Life in America, December, 1910; March, 1913

[11] The New York Times (New York, New York) Saturday, May 6, 1905

[12] Sunday Oregonian (Portland, Oregon) June 11, 1905

[13] The New York Times (New York, New York) Saturday, May 6, 1905

[14] Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon) May 29, 1921

[15] Moving Picture World, July 11, 1914

[16] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) Wednesday, April 30, 1913

[17] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) April 25, 1913

[18] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) Wednesday, April 30, 1913

Moving Picture World, September 19, 1914

[19] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) Friday, November 7, 1913

[20] Motion Picture Magazine, March 1914, pages 105-106

[21] Moving Picture World, July 11, 1914

[22] Photoplay Magazine, July, 1917

[23] Motion Picture Studio Directory, 1918

[24] Exhibitors Herald, January 22, 1921

Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon) July 4, 1920

Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon) May 29, 1921

[25] Moving Picture World, October 31, 1914

[26] Variety, November 5, 1915

[27] Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon) May 29, 1921

[28] Morning Oregonian (Portland, Oregon, March 20, 1900

[29] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) Friday, November 24, 1916

[30] Exhibitors Herald, September 3, 1921

[31] Exhibitors Trade Review, July 12, 1924

[32] Variety, October 25, 1918

[33] Variety, January 20, 1926

[34] Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon) May 29, 1921

[35] New York Clipper (New York, New York) March 15, 1913

[36] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) Wednesday, April 30, 1913

[37] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) April 30, 1913

[38] Santa Cruz Evening News (Santa Cruz, California) April 25, 1913

[39] Motion Picture News, June 26, 1915

Altoona tribune (Altoona, Pennsylvania) July 5, 1915

[40] Allan Dwan and the Rise and Decline of the Hollywood Studios, by Frederic Lombardi, McFarland & Company,

2013, page 47

[41] Motion Picture World, September 4, 1915

[42] Motion Picture News, October 21, 1916

[43] Photoplay Magazine, October, 1924

[44] Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon) January 20, 1918

[45] Motion Picture News, May 13, 1915

[46] Motography, March 4, 1916

Motion Picture News, October 21, 1916

[47] Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon) January 20, 1918

[48] The Lincoln Star (Lincoln, Nebraska) Sunday, May 14, 1922

[49] Motion Picture News, May 1, 1915

[50] Wid’s Year Book, 1921-1922

Film Year Book,1922-1923

[51] Hollywood Reporter, October 12, 1929

Hollywood Reporter, May 29, 1933

[52] Variety, October 12, 1927

[53] Variety, February 12, 1936

[54] Daily Republican (Rushville, Indiana) March 3, 1914